12-20-1980 – Melody Maker

Interviewer: Patrick Humphries

Apocalypse Brum

“Private faces in public places, Are wiser and nicer Than public faces in private places.” W.H.Auden.

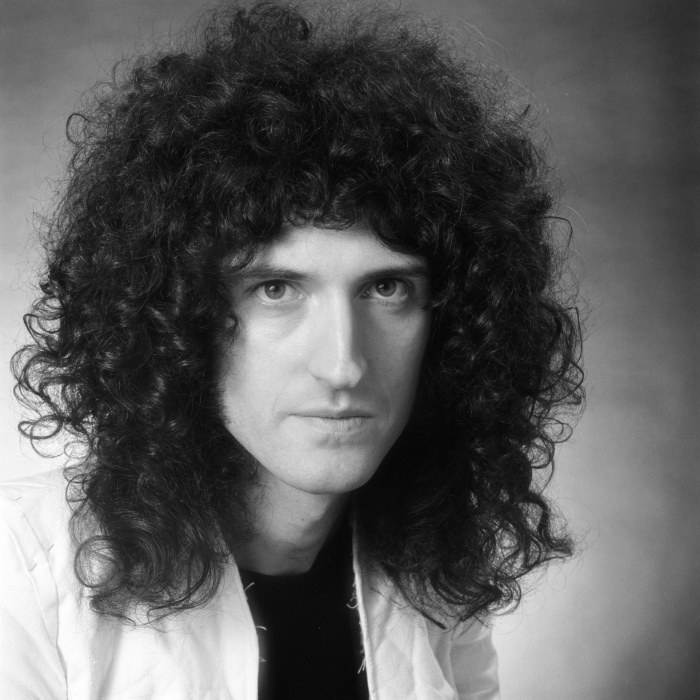

Not always true I admit, but it does go some way to illustrating the dichotomy between the private and public faces of Brian May.

Offstage, May is a quiet man, precise in his choice of words, a proud father, his thin white face framed by the familiar mass of curly black hair.

But once onstage, he is transformed into the guitar hero incarnate, the sole object of attention during one of his blistering solos, the target for thousands of hands, eager to touch the man or guitar responsible for that distinctive sound.

Queen are a phenomenon. “Another One Bites The Dust” managed to top both the American soul and disco charts. Every single and album released manages to make an impressive chart showing both here and abroad.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” still holds the record as the longest number one of the last decade, a tongue in chic single, which launched a spate of similar lesser epics, and made one appreciate just how clever Queen’s rocking operatic ballad actually was.

They have recently completed the soundtrack for the “Flash Gordon” film – the first rock band to actually tackle such a major film project. With so many Mega-bands talking about how they’d “really like to get back and play the smaller venues,” Queen actually did it last year with their “Silly Tour”, which included such unlikely places as Tiffany’s, Purley. They have a following here which is as impressive in its fanaticism as it is extraordinary to those outside it.

They have attracted probably more critical vilification than almost any other major band as they continue to pioneer their own brand of over-the-top, symphonic rock. A style of music which appeared increasingly redundant in the wake of the post-punk explosion.

Queen were an ideal band for the iconoclastic late Seventies bands to react against: their sumptuous light shows, addiction to dry ice, Mercury’s camp posturings on stage, lyrical pretentiousness, all combined to make Queen an easy target for those who wanted rock honed down to some sort of basic excitement.

Queen are either guardians of a school of epic rock which should have rumbled like the walls of Jericho when the first note of the punk fusilade sounded. Or they are a fascinating indication of how a band can survive the fluctuations of rock ‘n’ roll fashion.

Their antipathy towards the music press is well known, and consequentially they are not an easy band to pin down. Backstage at Birmingham’s National Exhibition Centre, they are surrounded by a security organisation that makes the SAS look like the Boy’s Brigade!

To while away the time before the gig, I sat out front and watched the band wrap up their sound check. Notoriously pedantic at the best of times about such things, Queen were even more precise on this occasion as it was the first time the NEC had been used as a rock venue.

Amplifiers were stacked high onstage as well as monitors suspended over it, there was enough cable laid to keep NASA in business and a lighting rig that – when fully ablaze over the audience – looked like the Mother Ship from the last reel of “Close Encounters”.

Huddled in conference around the drum podium, casuall dressed, were the four members of Queen, while the vast, empty auditorium rattled with the activities of roadies, lighting crews, promoters (Harvey Goldsmith, in person as himself), ushers, security staff and minders. Strange to think that the epicentre of all this activity were the four unostentatious figures clustered round the drum kit.

The gig itself proved a spectacular event, but raised in me a number of nagging questions about the occasion.

Just how harmless is an event like this, where the audience seem entirely content at being manipulated? Is Mercury’s habit of letting lucky members of the multitude actually touch his mike-stand an umbilical communication? Or is it a patronising acknowledgement of the space between him and his audience?

Isn’t the shapeless electronic morass which constitutes the central part of “Get Down, Make Love” rather unnecessary? Is there a justification in the band quitting the stage during the operatic section of “Bohemian Rhapsody”, leaving the audience applauding an empty stage?

(It reminded me of when Elvis Presley was in the army, and his empty Cadillac was sent on tour of the States – the oyster shell removed of the pearl!)

Finally, can the very nature of an event like this (remote spectacle and audience manipulation) be vindicated with “Well, that’s entertainment”?

What certainly is entertainment is the new film of “Flash Gordon”, to which Queen have contributed the soundtrack. Due to the other members involvement in diverse projects, it was Brian May who was the prime mover in getting the soundtrack together. He saw about 20 minutes of finished film, thought it looked “very good and over the top” and would be an edeal vehicle for Queen’s filmsoundtrack debut.

“We wanted to do something that was a real soundtrack… It’s a first in many ways, because a rock group hasn’t done this type of thing before, or else it’s been toned down and they’ve been asked to write pretty mushy background music. Whereas we were given the licence to do what we liked, as long as it complemented the picture.”

May did admit it was strange for the group who have complete autonomy in the studio when making an album – to collaborate so closely with director Mike Hodges and, particularly, arranger Howard Blake, who scored the orchestral arrangements, as Queen had never worked with an orchestra before.

May feels that the “Flash Gordon” soundtrack is a Queen album, and that it stands up outside the context of the film and that the average Queen fan won’t be disappointed.

Which brings me – rather neatly I think to May’s idea of who the average Queen fan actually is. The band, he claimed, meet “the more devoted side” through their fan club.

“But the average Queen fan probably wouldn’t feel like going along to the fan club, they’d rather appreciate us just for the music, I think. It’s a big cross-section, and by now we’ve picked up from all walks of life, all ages. Each time we put out a single it’s a little trailer, and different people become interested.

“When ‘Crazy Little Thing’ came out, a lot of young people – who probably regarded us as an older persons group – discovered they could get into our music…I was discussing it recently with somebody who wanted to start a fan club in Germany, which led to a discussion about what the fan club was. To make it a vehicle for…positive criticism, I suppose, and also a personality thing.

“Our fan club is more an information service, a line of communication. It’s turned into a pen pal organisation, which I don’t put down at all, I think it’s very nice… Our fans in Portugal writing to fans in Japan, which I think, in our little way, is a good thing. I think that’s one of the positive things a rock band can do, generate that feeling of being together.”

The positive side, sure, but what about the other side, the power a band like Queen exercises over an audience?

“Yeah, I know what you mean, we do have a lot of power. We just hope we can divert it in the right direction… I know it looks like a Nuremberg Rally, but our fans are sensible people, they’re creating the situation as much as we are, it’s not that we’re leading them like sheep. Especially up here ( Birmingham) they like to come along and sing, it’s a community feeling.”

What did Brian May feel Queen actually contributed to music?

“It’s very simple really, you just play music which excites people, which interests them. It’s rock’n’ roll, there’s no philosophical reason why we should be there…

“The flashy thing, that if it looks good and is well presented, then it can’t really have a substance… A couple of years ago that was at its peak, that if you had a decent light show and a good PA, that was selling out to commercialism. I think people have got over that, the groups that were successful from that period have started to go down the road we’ve gone down.

“If people are paying to see them , it’s worth being able to be heard properly and seen properly. It’s worth doing a complete show that people are satisfied with.”

Did he feel that Queen were short-changing their British fans, with, on average, one album and tour a year?

“Well we do on average 100-150 gigs a year worldwide… Queen is a yearly cycle of recording and touring, this year there was the film.

“Touring is certainly the most immediately fulfilling part of what we do, and it’s not really a big strain – mentally or physically – because we’re well organised, we know how to do it. All you have to worry about is playing well on the night. For me, it’s by far the best part of being in the band. Suddenly life becomes simple again!”

Did I detect, from that, the sound of a frustrated rock ‘n’ roller, who’d be happier playing The Hope and Anchor on a Friday night? he smiled.

“Well … It might be that feeling somewhere inside me, but I’m not so naive as to think that if I got that kind of life again I’d enjoy it… I wouldn’t really. Obviously there are times when you think life’s too complicated, everthing’s a big event.

“On the whole I wouldn’t have it any other way; you get a chance to do things that no one else can do. You know, you’re pushing forward in some way,” he laughed. “Maybe that’s naive as well…

“I think you need the balance, you need the studio to develop ideas… But there is always somewhere new to conquer, as it were, for instance this hall.

“In the Spring we’re going to South America where we’ve never been before, a whole new territory… We’ve been offered nothing less than 10,000 seat arenas, and most of it is 100,000 a night stadia.

“As you know, we’re not that keen on doing those stadium type gigs, but when you realise there’s that demand, and that no one else has really done it… I remember going to Los Angeles the first time, we sold out a couple of nights in a small place, and I went to see Led Zeppelin at the Forum. And I thought then ‘Jesus Christ, if we can ever play here, that would be the ultimate dream come true!”

“It’s an aim that affects everybody, even if they won’t admit it, that you’re progressing, you get to play Madison Square Garden for one night, then two, then three. You’re reaching more people each time, and it’s a recognition that the people who enjoyed themselves the first time had come back and brought their friends. It’s a good feeling to build all the time.

“It doesn’t mean that in some ways you’re not conscious it’s not an artificial aim, you know, getting bigger is not the Be-All and End-All. Often if you sell more records, it doesn’t mean that the quality of the record is any better, sometimes quite the opposite. But it’s something you do, another little force that propels you along.”

Despite Queen’s lack of a manager, the organisation that surrounds the band (which May described as “a sort of cross between a circus and an army”) does make it difficult to reach them. The sort of delaying tactics adopted – “You can talk to Brian at the hotel after the gig!” “You can talk to Brian at the venue before the gig!” – are that of a doctor protecting a hypochondriac’s best interests.

“We do have a reputaion of not wanting to talk to people, which is really not that true most of the time. If we have time, we’ll always talk. But if sombody slags you off in a way you don’t think is fair, you don’t want to talk to them again…”

But what about the challenge in trying to convince someone who thinks that – say – the Clash are the greatest thing since penicillin, is there not a desire to convince them of what you think Queen are worthy of serious attention?

“I’ve been through all that. I don’t know if it’s because I’m naive, but I did think that in the beginning it was important to keep the lines of communication open, to talk to everbody. In the end though, after many experiences, you find that it really doesn’t come out. If the guy has stated already that he hates you, and can’t see anything in you that is worthwhile, then nine times out of ten, if you spend your time trying to convince him how good you are (which is silly anyway), he goes away and writes what he thought anyway…

“Contrary to what people think, you don’t tour just to make money, or be adulated, or whatever. You need a very postive drive to keep yourself convinced all the time that it’s worth doing yourself. So if we didn’t think that the music was still getting to new places or doing interesting things, then none of us would feel like doing it.

“I don’t think that any critic can be more critical of us than we are anyway. If we’re coming up with ideas, then one of us will be so cutting and caustic about it while it’s being done that nothing much gets past if it’s in any way suspect. By the time it gets to the public, it’s been through all that.”

I wondered if it was the punk backlash against bands like Queen that soured their relation with the music press, who – at times – seem to resent their very existence?

“There are lots of little mechanisms built into relationships between a musician and the press, which means – almost inevitably – that you fall out. But it happened very early to us, so perhaps it doesn’t apply.

Generally, I could write the revies of our albums, the good ones and the bad ones – this sounds very bigheaded, ‘Arrogant Queen’ again!… It’s a very limited view of what goes on , as soon as something becomes successful, it can’t be worth anything… But I know that’s human nature, it was the same sort of cliquey thing when I was at school, certain things are ‘Uncool’.

“It’s one of those things that binds a clique together, rejecting everthing outside it… Part of what binds you is your beliefs, but probably even stronger are the things that you reject… I know I was exactly like that.

“We thought we were very big and clever because we booked the Troggs at college, and it was like they were so bad they were good. Which is unbelievably ignorant and arrogant, and it’s totally false as well.”

It was around this time that the minder came in to get Brian May ready for his job as guitarist with Queen, and the interview was terminated. For two hours, from Block E, Row Y and Seat 6 I watched ten and a half thousand people idolise Brian May as he peeled off the scorching solos which were manna to the thousands of raised hands.

May agreed to talk with me after the show, and it was back to the draughty dressing room to chat about the gig. He felt the audience were inhibited and wasn’t happy about the quality of the sound. The whole band felt that there was not sufficient new material embodied in the set, but were – as always – pleased with the audience reaction to songs like “We Are The Champions”, and how football crowds have adopted it as well.

“The Detroit Lions adopted ‘ Another One Bites The Dust’ as their team song, even released it on record. But then they started losing!”

How does he reconcile the obvious difference between himself as a person and the guitar hero of thousands onstage?

“I used to think that there were people, a breed of person, who was a ‘Star. But the more I’ve met people who I thought were ‘natural’ the more I realise that everyone puts on an act to some extent. Nobody can be exactly natural on stage.

“Even that naturalness we were talking about earlier is a pose, because it’s not natural. It’s not like you’re walking down a street, there’s 10,000 people looking at you… But the nice thing about rock music is that it does carry you away yourself.”

Finally, what about the ‘Exit Stage Left’ business during “Bohemian Rhapsody” and the over the top, Busby Berkeley production?

” ‘Rhapsody’ is not a stage number. A lot of people don’t like us leaving the stage. But to be honest, I’d rather leave than have us playing to a backing tape. If you’re there and you’ve got backing tapes, it’s a totally false situation.

“So we’d rather be up front about it and say ‘Look, this is not something you can play on stage. It was multi-layered in the studio. We’ll play it because we think you wnat to hear it’… We’re not into the over the top production for the sake of it, but because it highlights the music, that’s the object in our eyes.

“It’s not really the same approach as Kiss, where I would say the show is everything, although it probably doesnt end up looking a whole lot different. Our idea is to get all the impact of the music across in that short time. It’s only once a year, and you really have to try and emphasise every note!”