10-16-1988 – The Times – Mercury falls for a classical trap

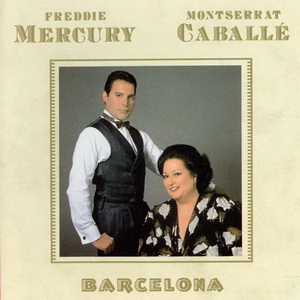

Freddie Mercury puts his operatic manner to the test with Monserrat Caballe in their epic version of the hit single Barcelona.

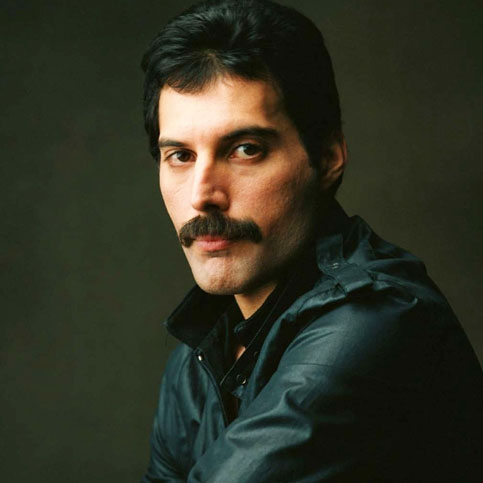

ONE of the most interesting ways in which pop is showing its age is in its increasing readiness to make peace with the old enemy, classical music. Last week, for instance, no sooner had Jean-Michel Jarre finished playing at choirs and orchestras in London’s Docklands, than along came Freddie Mercury ear-splitting vocalist with Queen offering his impression of An Opera Singer.

To be fair, Mercury has cleverly spread the load by again teaming up with the real thing: the same illustrious Spanish diva, Montserrat Caballe, whom he first inveigled into a duet 18 months ago on the hit single Barcelona. Now Barcelona has grown into an album of the same name (Polydor POL281, all formats) for which this decidedly odd couple has devised seven more fortissimo workouts. Largely written by Mercury himself, they bear the hallmarks of that overblown cod-operatic manner he has been toying with ever since Queen hit the jackpot in 1976 with the grandiosely-titled Bohemian Rhapsody, a fanciful and intricate piece of nonsense.

Popular though Barcelona will probably be in Spain and among Mercury’s vast international fan club, its ponderous orchestral manoeuvres are a little too reminiscent of the soundtracks to old Hollywood epics to find favour among opera lovers. The singing is perhaps best approached as a deadpan, high-camp joke.

Like Jarre, Mercury’s game is creatively or, if you prefer, wilfully to misunderstand the nature of classical music. What he enjoys and envies it for are not its rigorous and lengthy unravelling of a single theme, nor even its subtle dynamic shading: he goes for that aura of assertive pomp and circumstance which is beyond the reach of power chords and multi-tracking. The triumphal biff-bam-pow of, say, the loud passages of Beethoven’s Fifth are, I suspect, just the sort of thing any culturally ambitious heavy-metal musician might take a shine to. And aside from all the uninhibited bellowing it sanctions, the operatic angle here offers a nice costume opportunity to a confirmed fancy dress artist: as the album cover reveals, Freddie cuts quite a dash in black tie.

But pop/classical crossover doesn’t, thankfully, always have to be like this. Away from the heavily hyped posturing of the stars, genuine progress is being quietly made in overcoming music’s own informal system of apartheid. Composer Simon Jeffes’ eccentric octet, The Penguin Cafe Orchestra, is in the middle of one of its periodic forays into the limelight with a live album just out, When In Rome… (editions EG, EGED56, all formats).

Recorded last year in the Festival Hall, this, in effect, tells the story so far of the Penguin Cafe Orchestra: how, back in the early 1970s, long before world music became a media event, Jeffes made the delightful discovery that an elegant renaissance air could be successfully mated with a Venezuelan folk shuffle. The result, Giles Farnaby’s Dream, is the oldest example here of 16 timeless essays in classical-folk fusion, sans frontieres. Hybrid vigour is the keynote and the playing is suitably brisk.

A previous Penguin project gets a reprise from Thursday, with the return to the Royal Ballet of wunderkind David Bintley’s Still Life At The Penguin Cafe inspired and built around a series of Penguin Cafe tunes. These have been specially re-arranged by Jeffes for a house orchestra which can’t rely, as his does, on the assistance of ukeleles, banjos, bass guitars and elastic bands.

There is, however, more to the Penguins’ music than its whimsical alignment of sonorous, serious violins with ethnic folk instruments and found objects often suggests. Jeffes is trying to make the point that Western orchestras have sacrificed rhythmic agility and charm to the pursuit of size and volume the same type of criticism, in fact, that regularly gets levelled against heavy metal bands. And in a sense, the Penguin Cafe Orchestra would like classical music not to be all the things Freddie Mercury likes to think it is.

When I saw Still Life performed earlier in the year, the Royal Ballet Orchestra seemed rather stiff and undecided as to where it stood in this debate. But as an introduction to Jeffes’ hauntingly sentimental, circular melodies, Still Life is fine. And as an imaginative alternative to a video, the choreography, zoological characters and Green message are both sympathetic and strangely moving a view evidently shared by the Royal Ballet, since the piece is now a repertory item.

Embarked on exactly the same crossover journey, but in the opposite direction, the brilliant but austere Kronos Quartet from San Francisco has succeeded in making some extraordinarily difficult modern music from Bartok forwards acceptable to a rock audience. The patronage and enthusiasm of David Bowie and Sting, among others, has undoubtedly helped their mission to “open ears”. So has their regular encore: a thrilling arrangement for string quartet of Jimi Hendrix’s Purple Haze. But the far larger, more arcane side of Kronos’s repertoire encompasses northern composers such as Sallinen, Part and Schnittke, who must sound to the average pair of pop ears like aliens from another planet.

And yet the last time they played in Britain in July, they supported Bowie and were granted an astonishingly warm reception by the crowd. I think they appeal, in the way that some of the original psychedelic bands did, to the rock audience’s appetite for a good, occasional dose of absolute bemusement. You are never quite sure what Kronos is going to do next, or often what on earth they are up to at all, since the noises they coax from their acoustic instruments make most electronic effects sound tame and predictable by comparison.

How many rock fans will want to rush out tomorrow to buy Kronos’ new and more than usually uncompromising album, Winter Was Hard (Elektra/Nonesuch K979-1811, all formats), I don’t know. But I do hope Freddie Mercury is among them. For all its longueurs, there is at least no trace of glibness here.

Kronos Quartet plays the Royal Festival Hall on November 2 with the American avant-garde composer Steve Reich.