11-17-1996 – Sunday Times – Star Of India

Sunday Times Magazine

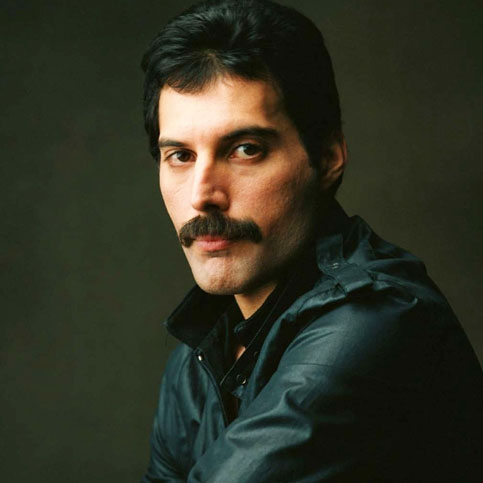

Freddie Mercury was one of the most electrifying performers in rock. But just as he tried to hide his homosexuality, he managed to avoid claming the crown of Britain’s first Asian pop star. This revealing set of photographs, published exclusively, is part of an exhibition that is about to travel the world. Waldemar Januszczak profiles an immortal showman

Saturday evening arrives, and Britain falls into its weekly stupor in front of the telly. Luckily it’s time for Gladiators, where a sprightly contestant is getting the better of Warrior on the bash-your-brains-out beam. As 300lb of brightly Lurexed behemoth plunges earthwards, the audience cheers, the contestants cheer, Ulrika and John cheer, we at home cheer, and somewhere up in heaven Freddie Mercury prepares to lead the lot of us into a mighty chorus of celebration.

Because – ugh, ugh, ugh – Another One Bites the Dust.

Now, I am as delighted as the next Gladiator-baiter that Warrior has had his butt bounced. Yet, having just met Freddie’s delightful family, I cannot for the life of me understand how a sweet Indian schoolboy from Zanzibar managed to sneak himself so successfully into the lumpen heart of middle England.

Certainly, the fact that Freddie Mercury was Britain’s first Indian pop star is too little known and appreciated. In my view it explains a lot, and adds considerably to his achievement. If nothing else, it makes it easier to understand how he ended up wearing some of the things he did – the red outfit covered in all-seeing eyes, for example, which he donned for the video of It’s a Hard Life, and which one wag complained made him look like a giant prawn. Freddie himself always played down his Indian origins. In the few interviews he gave, he remained deliberately unclear about them.

In the official history of Queen, told breezily by Jacky Gunn and Jim Jenkins, and promising “Exclusive Interviews With The Band”, it is firmly stated that Freddie was born of Persian parents, which sounds pleasantly exotic but is stretching the truth as mightily as Freddie sometimes stretched the seat of his hot pants as he posed on the world’s largest stages. In fact, his parents were from Gujarat in western India, and they were Parsees, Indian followers of Zarathustra, the man-god who is best known to most European non-Parsees for speaking in riddles to Nietzsche. “Body am I entirely and nothing else, and soul is only a word for something about the body,” spoke Nietzsche’s unbelieving Zarathustra, foreseeing perhaps what sort of performer Freddie would become. Off with the shirt, out with the pecs and on with the show; that was international communications, Mercury-style.

Parsees can indeed trace their origins back to Persia, but only if they turn the clock back an entire millennium, to the 9th century in most cases, when the first boatloads of persecuted religious refugees from the northern deserts landed on the Gujarati coast. Since then, the Parsees have had a thousand years to become indelibly Indian. Which is certainly what Freddie Mercury was as well. He did not arrive in Britain until he was 17. And most of his formative years were spent a short bus journey from Bombay.

Gujarat is the province that has supplied more Indian immigrants to the world than any other. All the Patels of the world come originally from Gujarat. Patel is the province’s favourite name. Bulsara, Freddie’s real surname, is nothing like as common. In fact, his father, Bomi Bulsara, informs me that the name is taken from the small Gujarati town in which he was brought up. And when I get home from my meeting with the jolly and communal Bulsaras, from poring over family photographs with Freddie’s parents and sister, nephew and niece – the first such meeting the family has allowed since Freddie’s death – I take up my ancient Times Atlas of the World and there it is, north of Bombay, south of Ahmedabad: Bulsar, a tiny dot on a huge coast.

Parsees are famous for being good businessmen and for shaping the tireless city of Bombay in their own image. “The men,” insists the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “have light olive complexions, a fine aquiline nose, bright black eyes, a well-turned chin, heavy arched eyebrows, and thick lips, and usually wear a light curling moustache.” That’s Freddie all right. When asked by an interviewer if there was anything in his appearance he would change, he complained only of his teeth, which stuck out at the front. I see that he inherited those from his mother, Jer, who is tiny and very charming, and who announces proudly, “This was our baby” as all of us, family, trespassing journalist and Freddie’s English brother-in-law, Roger, gather in the Bulsara enclave of Nottingham to coo and aaah at her earliest pictures of the boy who would be Freddie Mercury. What a lovely, bouncy, bonny, beaming baby he was.

I had assumed Farok Bulsara had chosen the name Mercury because he imagined himself to be as un-catchable as quicksilver, whizzing and sparkling about the stage. The official Queen biography says he named himself in 1970 after the messenger of the gods. Roger, however, insists that he chose the name because Mercury was his rising planet. “When he told me, I said, it’s a bloody good job it wasn’t Uranus. Freddie never forgave me for that.” Kashmira, Freddie’s sister, gives Roger a look. He says no more on the subject.

There are all sorts of perfectly adequate reasons for becoming a famous pop star. Gigantic quantities of money can be yours to spend frequently and foolishly, or to lose if you choose, Sting-style. Sex is no longer the result of any kind of tiring chasing about: people offer themselves to you on a plate, men and women, day and night. You get to meet whomever you want, stay wherever you want, say no to whatever you want. And if drugs are your chosen poison – well, there is simply no better occupation for putting yourself into constant contact with them, except, perhaps, playing for Arsenal.

All of these are reasonably attractive benefits of the job, and Freddie, now we know, sampled them keenly. But money, sex and drugs are merely pleasures of the earth, briefly enjoyed, quickly passed. Even pop stars grow bored of them eventually. There remains one outstanding reason why achieving global fame as a topper of the pops is a maddeningly desirable goal. One opportunity offered by this occupation has proved irresistible. Beings like Freddie – legends of pop – have discovered a foolproof way to cheat death. They are immortals.

One of the many pleasing aspects of the Parsee religion is the entirely optimistic view it has of death. Parsees do not really see death as death. Instead they contend that a man’s life falls into two parts: its earthly portion, and that which is enjoyed afterwards. Bomi and Jer Bulsara, who are devout, ensured that Freddie was given a proper Parsee send-off after he moved to the next stage on November 24, 1991 – in the presence of Dave Clark, as it happens, a minor immortal himself, not because of all the face-lifts he has had but because he played the drums on Glad All Over.

“Freddie Mercury died peacefully this evening at his home in Kensington, London,” it was announced at midnight. “His death was the result of bronchial pneumonia, brought on by Aids.” That was it. It struck me then as distressingly to the point and, on the face of it, pretty conclusive. But anyone who has ever tried to gather a spoonful of the element with an atomic number of 80 that appears as Hg in the periodic table will know how difficult it is to catch Mercury. Death could not manage it any more conclusively.

So Freddie is not dead. He may not have been spotted in as many supermarkets as Elvis, but his fans are just as reluctant to let him go. Pop stars are immortal because they provide the soundtrack for other people’s lives. Some scream of theirs opens you up; some words they whisper, some advice they give, wedges itself firmly in your personal history. In particular, when it comes to the subject of love, nobody has your ear as clearly or as privately as a pop star. Certainly not your parents.

Farok Bulsara was not born in Gujarat. Bomi and Jer were travellers and their beloved Freddie-to-be arrived on the East African island of Zanzibar at the government hospital, on September 5, 1946. Bomi worked in the Zanzibar High Court as a cashier. Most biographies of Freddie, say that his given name was Farookh, but it was Farok, insists Roger. Kashmira is a polite and petite Nottingham housewife who looks like Freddie in a wig. Her children look like Freddie as well, and not at all like Roger, who is stocky and blond and works for an airline. The Bulsara genes are clearly made of insistent stuff.

In various fascinating ways, Freddie’s life has been gathering momentum since his death. The same digital technology that made it possible for Lennon to continue adding to his song catalogue in those weird “Threetles” comeback singles also brought us an album’s worth of new Freddie songs last year. It was called Made in Heaven (well, they could hardly have called it Made in a Computer). On the album he was backed by the remaining members of Queen. It was a revealing and heartfelt package, and therefore the least Queen-like of Queen’s albums. In truth, neither love nor introspection was Queen’s forte. Their forte was the sort of music that makes stadiums shudder. We Are the Champions, they chanted. We Will Rock You, they promised. When Queen surfaced in the 1970’s, football crowds took to them immediately. But Made In Heaven was different. Freddie had written the songs in a hurry, in the last months of his life, and you sensed that he was trying to be honest in them, at last. “My make-up may be flaking but my smile still stays on,” he warbled. The outstanding song on the album, the last song he wrote, was called Mother Love.

He was a loyal family man who liked to surround himself with photographs of his nearest and dearest; a good son and brother who remembered to phone. These photographs, impeccably and expensively framed, were displayed around his Kensington house. Many were collected on top of his grand piano, the one on which he can be seen teaching his niece to play the EastEnders theme in one of Roger’s delightful family snaps. Freddie had his boyfriend, Jim Hutton, make some tables to accommodate his special pictures. Freddie loved photographs. And photographs loved him.

I am shown another lovely one of Freddie as a small boy, standing with an unhappy-looking Kashmira. Behind them is a long, low railway bridge. All around is sand. That’s Bulsar. The fleeing Persian followers of Zarathustra came to this coast in small numbers and have remained a tight community ever since. It is estimated that there is only around 100,000 Parsees left in the world, the smallest congregation of any of the world’s principal religions. When Queen performed at Rock in Rio, they played live to nearly three times as many pop fans as there are Parsees. Live Aid, still the world’s largest televised pop concert, at which Queen were widely considered to have stolen the show, was beamed to 170 countries on July 13, 1985, and they reckon Freddie’s romping was watched by over 1.5 billion fans. This is twice as many people as watched Neil Armstrong become the first man to walk on the moon. This is fame.

The photograph on the beach at Bulsar is followed by many others, black and white, tiny and scratched (for they were before the Queen computers began enhancing them), fascinatingly different from the ones we are used to seeing of the putative Persian. There’s Freddie with his nanny, Sabine, in Zanzibar, Freddie in a rickshaw on the way to the Fire Temple; Freddie coming second in the high jump. In all of them he looks smilingly, toothily crisply and unmistakably Indian.

When he was seven, he was sent to a boarding school 50 miles from Bombay. He remained there for 10 years. His parents continued to live in Zanzibar and only saw him for a month every summer, when he returned for his holidays. In the first photographs at boarding school he appears understandably vulnerable; a very young boy, with very skinny legs, very far away from home. By the end of his time at St Peter’s he had become something of a spiv, lounging on a garden bench in dark glasses, being glamorous for the first time.

St Peter’s was private and English. It was here that Farok began to be called Freddie and started his first band, the Hectics, apparently named after his naturally exuberant playing of the piano. For my money, Freddie never looked cooler in his life than he did lining up with four other Indian lads in matching quiffs and casuals, pretending they were the Platters. Farok Bulsara’s excellent adventure – the one that turned him into one of the most popular performers the world has seen, a very rich man capable of spending a million pounds on a single shopping spree in Japan – began properly in this hot outpost of England, in which he also took up boxing and, predictably, had his first homosexual encounter.

Although he was outrageously camp in private, Freddie had always been coy in public about his sexuality. No, not coy: misleading. He certainly kept it hidden from his parents. In all the photos I see of the many Bulsara gatherings he attended, he is accompanied by Mary Austin, the former boutique worker whom he dearly loved, with whom he once lived, and to whom he left the bulk of his estate. Jim Hutton, the live-in lover who nursed Freddie through the worst years of his illness, is nowhere to be seen.

This was the curious side of him, the side that always appeared to be in fierce denial on matters of sex and race. Despite his own Indian origins, or perhaps because of them, Freddie and Queen were one of the first bands to play in Sun City in South Africa at the height of the apartheid regime. The official announcement that he had Aids came only 24 hours before he died. Until then, he continued to be, in the words of his best-known solo hit, the Great Pretender.

Gay pop stars who trade on their sex appeal obviously feel extra-conscious of the need not to alienate their female fans. But Freddie, you sense, was more concerned with keeping the truth from his family. Like Elton John, he was one of those flamboyant stars operating under an assumed name who was widely known to be gay but who had some difficulty coming out. Hutton’s book, Mercury and Me, has been very unpleasantly serialised in the tabloids, and if you believe what you read in The People then it is a typical kiss-and-tell of the 1990’s, filled with lurid descriptions of Freddie’s decent into a lifestyle of hunks and coke. But the tabloids have had to work hard at filleting Hutton’s memoir to emerge with this much dirt. I found it a sympathetic read, warm about Freddie, and the author’s love for him. Warm, too, about Freddie’s weekly visits to his parents in Feltham, where his mother always ensured that he took away a lunchbox filled with her cheese biscuits.

Jer Bulsara expected that Freddie’s memory would live on in some small way after his death. “I thought, in one or two years, people are going to forget my Freddie.” But they are not going to forget. Letters are sent to her old house addressed only to “Freddie Mercury’s Mum and Dad, Feltham”, and they reach her. She reads them, and you feel that they have helped her see at last what her Freddie meant to people.

Jer wanted the small terraced house in which they lived after they all came to England to become a Freddie museum, but Feltham council was not interested. Somebody paid to have a special commemorative bench set up, but that was quickly vandalised. Bomi and Jer remain a jolly and open-hearted pair, plainly delighted at seeing their Freddie again in all these photographs. Among the assembled, Kashmira is the one who appears most protective of Freddie’s reputation, and most suspicious of me. In her hall she has assembled a small shrine to Freddie on a coffee table, with all the medals he won at school for boxing and jumping, and the bronze statue that stood in for him on the cover of Made in Heaven, the one on which he is wearing his shiniest posing gear.

Irena Sedlecka answers the phone with a laugh, and begins carving out bold new shapes for me from old bits of the English language she has picked up. Irena is Freddie’s sculptor. She made the statue on the cover of Made in Heaven, now sitting on Kashmira’s table in a very nice road in Nottingham. Like Freddie, Irena arrived in middle England from somewhere distant and different. Trained in Prague, she first made her living working for the Czech communists in the early 1960’s producing pieces of heroic socialist statuary to dot about the capital. Her best-known work was at the Lenin Museum, for which she made the beliefs on the front of the building, and the statues of workers, farmers, marines, mothers and children and other heroes of the socialist revolution on the roof.

Irena came here in 1966 and has been increasingly in demand making realistic statues of assorted heroes of British public life: Bobby Charlton, Duncan Goodhew, Jackie Stewart. She says she is a little too old to know much about pop music, but she saw Freddie on Live Aid and liked him “because he looked like a real man”.

Hmmm. She is obviously one of the many women who fell for Freddie’s off-with-the shirt, out-with-the-body routine. On stage he never stopped moving, swinging that mike, fondling those watching imaginations, male and female. Since those things are expected of pop front men, it has to be said that he was one of the best there has ever been. In Britain, Jagger was his only rival when it came to teaching part-time ravers how to overreach themselves at parties.

Irena is now enlarging Freddie to 8 ft tall, to go on a plinth in Montreux, near the studio where he recorded his last songs, next to the lake. Her Freddie is a creature of the stadiums, arms raised, fist clenched, muscles rippling, heroically intense. I am afraid it is the Freddie I like the least. The one I like the most appears in Roger’s photographs of family gatherings, teaching his niece to play the piano, celebrating his fathers 80th birthday, smiling in front of the Christmas tree. Roger’s family snaps are going to be appearing alongside those of Snowdon and Bailey, in a travelling exhibition of Freddie photographs organised for the Mercury Phoenix Trust, a charity set up by the other members of Queen to do what Freddie himself did not: endow and finance Aids relief.

Freddie would have been 50 this year. According to Pliny the Elder, Zarathustra “laughed on the very day of his birth”. So did Freddie, and he was still laughing a year later when and Indian photographer in Zanzibar took his picture and won a prize with it. Jer remembers that the photographer was so pleased with this beaming baby that he put him up in his shop window, so perhaps this counts as Freddie Mercury’s first public performance.

When Zanzibar began to agitate loudly for independence from the British, Bomi and Jer and most of the sultanate’s other Indian households decided to flee. They had six months to settle elsewhere before their passports ran out. Freddie was all for going to England. Jer remembers that he had grown bored of spice-free summer holidays in the spice island, and would complain that there was nothing to do. As a small child, he had been happy enough to play on the beach. But it was no longer enough.

So the Bulsara family moved from Zanzibar in the Indian Ocean to Feltham in Middlesex. Feltham is one of those suburban traffic-light towns you pass when you leave London in the general direction of Slough. It sits under the flight path of Heathrow Airport, and if you sat down with a marker pen and tried to find the place in Britain that provided the most striking contrast with Zanzibar, I doubt whether you would find anywhere much better to ring. The family bought a small terraced house there. Jer and Bomi continued to live in it until earlier this year, when they moved to Nottingham to be nearer Kashmira. They now live on the same road as her.

Feltham is small and used to be very friendly. In Saxon times the name meant “home in a field”, which still captures the mood of the place, if not its appearance. Jer had some difficulty adjusting to the change of climate. But she felt at home eventually and encountered no racism at all. It was 1964. Bomi found a job working for Forte’s at Heathrow, and Freddie would later work there as well. They were a typical family of East African Asians, soon to be joined in Britain by their fellows from Uganda. Jer obviously wanted Freddie to become a doctor or a Lawyer, and he obviously wanted something else. First stop: Ealing College of Art.

Another of the pictures going into the exhibition shows Jimi Hendrix sitting cross-legged in the corner of Freddie’s room at Feltham. Wait a minute. That isn’t Jimi after all. It’s Freddie wearing his beloved Jimi look-alike outfit, caressing a borrowed Fender Telecaster. Later on, he would become one of the world’s finest and most insistent air-guitarist. He was actually a gifted pianist. But his best instrument, the one he plucked and teased and strummed most effectively, was the audience at Queen gigs.

There are stacks of videos available at your Virgin Megastore of Freddie playing the people. “Queen Live,” here, there and everywhere. As one of the most successful pop groups of all time, they attracted constant attention, and because they put so much energy into the presentation of their shows they were a favourite with film-makers. Queen were not only the noisiest band of the Seventies, they also used the most lights, the largest stage sets, the flashiest costumes, the biggest crew and the latest technology. Freddie Mercury was spectacularly telegenic. The rest of the band knew how to keep out of the way and let him get on with it.

It was Freddie who persuaded them to adopt the shrill name Queen. Without his innate exoticism and unforced foreigness, Brian, Roger and John might have found themselves rocking amiably in a pleasant pop group but I simply cannot imagine them stretching all those boundaries. Before Queen they were called Smile, which sums up Brian and Roger well enough but offers no hint at all of the global frenzy to come. Transplanting levels of fantasy that belong to 1001 Arabian Nights to Feltham – that was Freddie’s achievement.

There is, I see, a popular Arab proverb that used to be repeated in the old East Africa, the one that was marked in red on old atlases, the one that Freddie came from.

“When you play on the flute in Zanzibar,” it claims, “all Africa dances.” This, I suggest, is only possible if you are using Queen’s sound system.