09-27-1975 – Sounds

WIMPY AND QUIPS

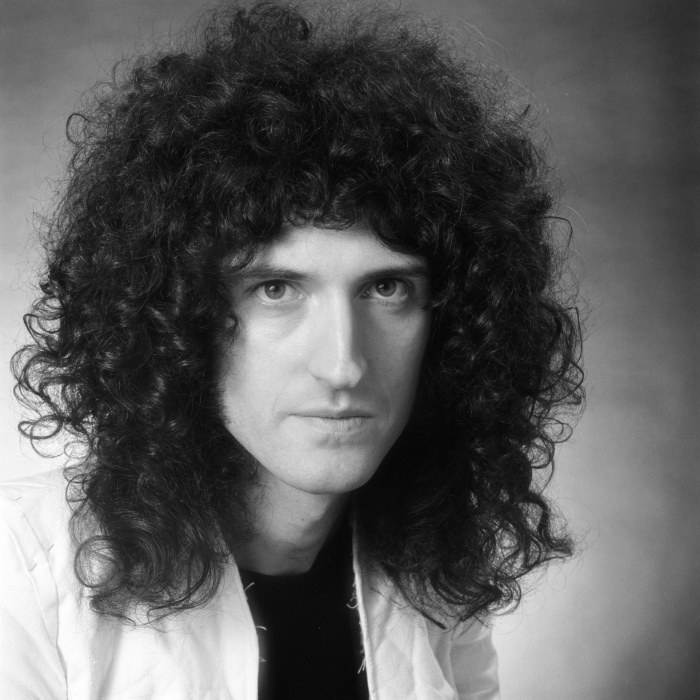

Jonh Ingham shares an Egg burger with Queen’s Brian May

It was an easy day; I was reading my old press clippings. The phone rang. I almost didn’t answer it but security can lull you. I picked it up. The voice was persuasive, it belong to a publicist. He was offering the mouth of a popstar. Business was slow, I took him up. We agreed on a price. I was given a time and address. The microphone wasn’t working–I tied the cord to the mike with a rubber band and it sprang into action. The batteries were fresh. I dropped into the tube and headed into East London. Sarm Studios had few pretensions: it was an efficient hit-making machine hiding out in an obscure basement.

Brian May was leaning against the wall conferring with several others, his blue work shirt was decorated with badges. He went into the studio to get his black velvet jacket; lying on an amp was the infamous .7 guitar. May confessed he’d had another built to the same specifications, meaning that it had to be played with the hand constantly damping the strings to prevent instant feedback. His jacket was also decorated with badges. We stepped outside; it was beginning to rain. We walked quickly round the corner to the Wimpy. He ordered an egg burger while I set up my recorder. A dilapidated character at the next table gave May the once over. The black velvet suit spoke its own language. His ashen Aubrey Beardsley visage and cherubic rats nest halo of hair added extra volumes — obviously one of those goddamn rock stars little girls go crazy for. He edged over to the end of the table. I turned around.

“Beat it bub. This is classified” He shifted back to the other end. I had instantly noticed that May spoke with a soft voice; the hubbub of conversation swirled around us disconcertingly loud. The muzak was like barbed wire being raked across the eardrum. I put the microphone extra close to May’s egg burger, pointing it directly towards his kisser. I thought for a moment, and then asked about Queen’s recent management hassles. The interview had begun.

“It affects your morale,” he replied. “Your capacity for working. It dries you up completely when you’re worrying about business things. We couldn’t write at all in that three months. We came back from Japan thinking, ‘Great, we’re going to finish the writing and then record it,’ but the whole thing with Trident blew up at that point, and we spent the next three months being businessmen, which is the last thing we wanted to be. But now it’s all sorted out — all the emotions came out in a big flood — and I think it’s going to be really good.”

What prompted the blow up?

“It’s been coming for a long time. It’s difficult to know what to say without being libellous. Mostly I feel less annoyed than disappointed. They’re a company which started out in a small way, but recently I think their holdings got too big for them and got on top of them. If we hadn’t got out we would have been trampled on. I think we saw it just in time.”

So you saw yourselves being swallowed up in that empire rather than receiving personal involvement?

“Yes, and not receiving our just rewards, and not getting treated right. It’s a great shame because the relationship used to be very good. We weren’t nasty about it at all. We said: ‘look, it isn’t working. We want to get out and we want to pay the price’. They got very emotional and it eventually got very nasty indeed and it got to the point where” — he paused for a long time, the muzak swelling up in the silence — “they just threw everything at us they possibly could and it developed into a war but (he smiled quickly) I think we won.”

It seemed to be going well. The chap was talkative, had a droll sense of humour. If only I could think of enough questions to last the distance. I decided to wrap up this business trivia and fired him a question about their new manager John Reid.

“We knew we were in a difficult position management-wise, but we were in a good position overall. So we went around and saw everybody that we could, and it just turned out that the only situation that was suitable for us, really, was John Reid. The whole framework suited our framework. It’s a difficult situation, being halfway in your career.”

Brian elucidated on ensuring activities: a November British tour, several nights at each venue, then to the States, Japan–“one of our favourite places at the moment”—where they perform in a couple of baseball stadiums, and then Australia and Europe.

I asked a truly hoary and creaking standard question: How do you see the last album as a progression from the last one?

He answered instantly. “It’s more extreme. It’s varied, but it goes further in its various directions. It has a couple of the heaviest things we’ve ever done and probably some of the lightest things as well.” He thought, a discordant violin sawing in the background. “It’s probably closer to ‘Sheer Heart Attack’ than the others in that it does dart around and create lots of different moods, but we worked on it in the same way we worked on ‘Queen II’. A lot of it is very intense and very … layered.”

I started to ask a question and it vanished into the mists. I stared blankly at Brian, ignoring thoughts that the questions had dried up. And they call this a living? A synapse came to the rescue. What of those rumours that you’re closing in on your second PhD dealing with astronomy?”

“No.”

What about your first one?

“I wish I had the time; it’s about 96 percent done. It breaks my heart because I get no time to finish it. It’s all written up, all the work’s done, but I can’t get that last bit done. For a time I could keep it up at the same time as the group, but it’s impossible now.” This was a matter that had long intrigued me. It seemed daft to pursue a course of studies when it seemed certain that the knowledge would never be applied.

“Well, at the time it didn’t seem like we had a chance. We weren’t really close to the music business. We were a band, but we didn’t have any contacts. We’d all done a lot of work in a band and never got anywhere. We thought: ‘well, it’s there, but we can’t get to it.’ And it was only gradually that we began to realise that something was happening. I think the Mott tour was the turning point, really.”

Such caution took me by surprise. It had seemed almost ordained from the beginning that Queen were On The Way Up. I shot him a quick one about the idea of giving it up for life as an academician.

“I didn’t want to give it up. We always knew that if we got the chance, we would. It’s always been a dream.”

Do you ever think you’ll utilise that astronomical knowledge practically?

“I hope so, I still keep in close contact with my astronomy friends, and I still read the periodicals. I hope to some day.”

I’d been a bit of an astronomy nut myself; I understood the fever. I asked his reasons for pursuing astronomy.

“It was another sort of childhood dream, I think. I was always interested in the stars. It just happened that the subjects I was best at were maths and physics. It was a momentum thing, which happens in schools to a certain extent. If you’re good at something then you’re shoved into it, and I then discovered that I’d got a physics degree and there was a place waiting in the Astronomy Department, so I thought: ‘must do it’.” He laughed softly and took another bite.

I checked the cassette. Godfrey Daniel! Hardly any tape had been used. I’d have to think of more questions!

“I really enjoyed it. I still think it’s as interesting as when I was a kid. It was part theory and part practise. It’s solar system astronomy; I was looking at dust in the solar system.”

Dust?

“Dust. There’s a lot of it around. I was doing stuff on motion of dust, using a spectrometer to look for Doppler shifts in the light that came from them, and from that you can find out where they’re going, and possibly where they came from. It has a lot to do with how the solar system was formed.”

Space jockeys all, we continued to talk shop. Brian dropping the fact that his research had helped establish that this dust had an orbit. I chuckled at how the boffins must feel about this budding scientist wasting his life in a rock band. He got up for another cup of coffee. I took the opportunity to check the tape back.

Mother of pearl! My voice was louder than his! It was there, though, that was all that mattered. He returned and I asked teeny-bop questions about Queen’s ultimate hysterical mob reaction in Japan.

“It’s good practise,” he summated dryly. The Olsen infatuation with fame surfaced: if Brian wasn’t interested in fame, what was

the point of playing in a macho ramalama band like Queen?

“The first ambition was to make an album. I wanted to make something that would last for generations, because I thought I had some worthwhile things to do. I was very, very keen on the guitar, and there were lots of things I wanted to do like harmony guitar parts, and there was no outlet. It was great to get the first album out, and having done that it freed our mines to actually start creating for its own sake. And the second album was, I think the most creatively dense thing we’ve done. It was done at a time when our heads were cleared of all the things we’d always wanted to put on record.”

I was running out of ideas. I decided to double back over earlier ground from a different angle. Queen’s fairly fast rise to power had always fascinated me — just who was manipulating who? When a band creates its own demand and an audience subsequently rushes in to fill the vacuum, is that audience aware of the manipulative wires, and if so does it care? Just who masterminded that, squire?

“Ooh, really hard to say. I suppose we did have a lot to do with it. We always argued over what we should do; and there’s a lot to being in the right place at the right time. The Mott tour was exactly the right tour to do. It’s very easy to say that it’s come out all right and would have done anyway, but you never really know what the contributing factor was.

“We’ve always been very demanding with the people we work with. If there’s something to be done we don’t generally sit back and let them do it, we interfere with them and make their lives hell (he gave a small laugh)… Everybody who works with us has to understand what we’re trying to do. It’s not just managing a band, it’s managing Queen, which is very different.” He laughed again.

“I’m very happy. The only thing I’m not happy about is not getting enough time to think on an abstract level. You have to tailor most of your thoughts to producing something, and it’s nice to think — what is it? — extrinsically as well as intrinsically.”