06-18-1977 – NME

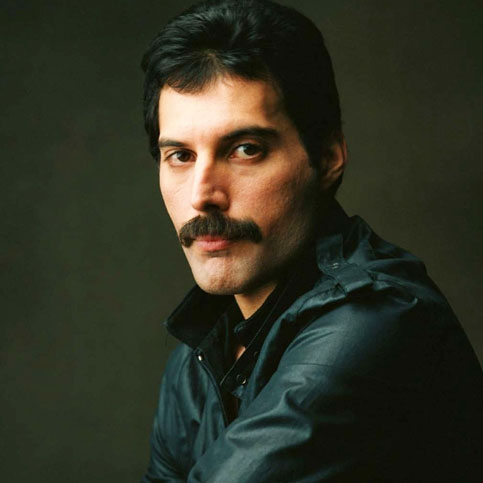

Freddie Mercury: Is This Man a Prat?

by Tony Stewart

FREDDIE MERCURY has always liked to dance the Millionaire’s Waltz.

There’s a story about him, dating back to his days as an impoverished student, which illustrates that even at that time he had grand aspirations for a luxurious existence. It was before Queen were formed and he was running a stall in Kensington Market with the delicately pretty drummer, Roger Taylor.

Apparently the venture was not a tremendous financial success and it perturbed Freddie that he would be unable to afford a taxi to take him home.

According to the fable he was so reluctant to undergo the indignities of public transport that he secretly sold Taylor’s jacket to pay his own cab fare.

Mercury doesn’t actually deny this story, but neither does he admit its authenticity.

“You’d be surprised how much of it is exaggerated and blown up by the press just to make good copy,” he explains, his fingers vigorously pruning his hair, as if in search of nits, as he relaxes on the patio of his manager’s Knightsbridge home. “I would give them a bit of spice and they would add all the trimmings.”

“My lifestyle and this very precocious nature was blown out of all proportion. But the media created a lot more than I could give. I was prepared to live with it, and it was up to me to make sure I had one foot firmly on the ground. I feel I have.

“It’s strategy. One has to use it to one’s best advantage, and I feel ummm…” Suddenly he breaks off, seemingly at a loss for words.

“Darling, if everything you read in the press about me was true then I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you today, because I would be so worried about my ego. Actually, if it was all accurate, I would have burnt myself out by now. I really would have.”

But you do appreciate the mystique which has developed around you. “I think I need it. I like all that. It’s my character. Certainly I’m a flamboyant person. I like to live life. I certainly work hard for it, and I want to have a good time. Don’t deny me that. It might not come again and I want to enjoy myself a little.

“I hope,” he adds, tilting his head and quietly smirking, “that when you better yourself in your profession you enjoy yourself too.”

Bitch!

That he agreed to do this interview in the first place was, in fact, something of a surprise, and the confrontation undoubtedly started with some mutual hostility.

My recent report of a Queen Hamburg concert on their European tour had not been received warmly in the Queen camp. Mercury had taken exception to being described as a “rock ‘n’ roll spiv” who used the band “as a vehicle for an elaborate exhibition of narcissism”. The basis of my criticism was that more importance was afforded their visual, than their musical presentation. And, Mercury had led them over the top with his self-indulgence, to the detriment of the group performance.

His answer is to make me feel as uncomfortable as possible when we meet. Firstly by insisting that his bodyguard, an intimidating bulk of muscle, is present, and secondly by his own attitude towards me. Seemingly he is determined that I should feel subordinate to him.

“I remember,” he opens, “speaking to you three or four years ago. That right? So you’re still working as just a writer. Don’t they have such a thing as…aha…promotion? Life is not treating you very well, is it?

“I would have thought,” he adds lightly, “that since the last time I met you, if you had any go by now you should have become…aha…editor of The Times or something.”

Well, Fred, it was offered, but you know how it is. “Tart,” he simpers quietly.

He then decides to bring my critical ability into dispute by insisting that Queen are trying to broaden the bounds of rock music. That’s why, he argues, he has recently had an identical copy of a Nijinsky ballet costume made. He’s not just posing, but using various artefacts of different cultures to make the band better and more entertaining.

“Which,” he adds indignantly, “you don’t seem to agree upon. You don’t leave any room for progression, do you?”

Well, I’m not sure if it is a progression, which is the basis of my criticism.

“Stuff your criticism,” he comments petulantly. “I think you look upon things with a very narrow view. I feel you restrict yourself by working in a very small framework. Have you ever reviewed a ballet show?”

No. I shouldn’t think I would be qualified to do so either.

“What makes you think you’re qualified to do rock ‘n’ roll? Do you need degrees to do it? If ballet should suddenly infiltrate rock ‘n’ roll, he confidently predicts, “you would be the first to jump on it, wouldn’t you?

“You don’t seen to grasp or have any sense of actually err…I just don’t think you know anything about style and artistry. Maybe they’re beyond you, therefore you can’t grasp them, therefore you dismiss ’em.

“I think that’s really a poor show from your point of view.

“It doesn’t worry me a bit! I just feel that you have terribly missed the point.”

BUT AS HE continues to express his indignation it becomes clear that his invective is far from personal, and he is merely criticising the rock press in general and venting his fury on me as the nearest representative at hand.

“You’re too narrow minded. You’re the bloody arrogant sods that just don’t want to learn. You don’t want to be told anything. You feel you know it all before it’s even happened.”

These ill-advised, inaccurate, not to mention unkind words, cannot be ignored. Mercury needs putting straight.

At a time, I tell him, of great musical change – when the New Wave is at the very least causing us all to re-examine our rock credo – Queen are alienating themselves from this very culture. Worst of all they appear to be guilty of the cardinal sin: believing their own myth.

A rock gig is no longer the ceremonial idolisation of Star by Fans.

That whole illusion, still perpetrated by Queen, is quickly being destroyed.

There is nothing more redundant, or meaningless, than a posturing old ballerina toasting the audience, as Mercury does, with “May you all have champagne for breakfast.”

“You hated that, didn’t you?” He replies with a light laugh, colouring slightly. “I loved it, and I think that people love it. It’s part of entertainment.

“God! You haven’t an ounce of artistry in your veins really.

“Can you imagine,” he asks, his voice shaking at the thought of such a horrifying prospect, “doing the sort of songs that we’ve written, like Rhapsody or Somebody to Love, in jeans with absolutely no presentation? (Precisely. – Ed.)

“You don’t seem to realise that the kind of public who come to see us love that kind of thing. They want a showbiz type of thing. In fact they’re the ones who put you on the pedestal.

“Why do you think people like David Bowie and Elvis Presley have been so successful?”

Because they give their audiences champagne for breakfasts?

“Coz they’re what the people want. They want to see you rush off in the limousines They get a buzz.”

(When in Oz last year Freddie was so aghast at having to walk 20 yards from the hire limo to the dressing room at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion, he smashed a full length mirror in a fit of pique).

When he was younger, Freddie explains, the myth was part of the rock ‘n’ roll excitement. Performers were untouchables, he suggests, and there was a thrill in being unable, for example, to get near Hendrix after a show.

“What do you expect? Somebody to go round and have tea with the front row? Break this barrier we’ve put across?

“God! You’ve missed the whole point.

“I’d like you to tell me how we (Queen) could better it if you think there’s too much of a barrier.”

Sack Muscles.

The thought occurred to me, but remained unaired. Why involve yourself in such bitchy rhetoric; and anyway I had no intention of inviting the bodyguard’s fist to play bloodbath with my face.

WHAT IS more significant is that on-stage Queen are no longer, ahem, majestic, and their last album A Day At The Races was mostly bland and insubstantial, musically and lyrically. Quite why they should have lost the artistic momentum they possessed on Sheer Heart Attack and A Night At The Opera is bewildering.

But surprisingly this is an observation Mercury partly concedes.

“It’s very difficult,” he acknowledges, “especially after five albums, to come up with totally outrageous and original things.”

Since our initial eventful, sometimes bitter, confrontation he has now mellowed slightly. Various complaints from both of us has been extensively voiced over the splendid fresh salmon lunch provided by the kitchen of Queen’s manager, John Reid. On returning to the interview Mercury’s dudgeon had diminished and he appears to be more rational and less sensitive.

“I think you’ve slightly misjudged us in what we’re trying to do,” he suggests mildly. “You’ve probably written about all our bad qualities and veered away from the point.

“I am not,” he emphasises, “using the band as a vehicle. I like to think we’re exploring different areas, and it’s also where our interests lie.

“I’m into this ballet thing, and that’s why I’m trying to put across this Nijinsky costume; and trying to put across our music in a more artistic manner than before.

“A lot of people just dismiss it and say I’m wearing a silly little outfit, rather than being critical and saying that formal ballet may not be quite right for rock ‘n’ roll.”

Why is it so important for you to radically broaden the scope of rock into other cultural areas?

It’s just,” he answers simply, “a logical thing. I want to do different things. I don’t want to keep playing the same formula over and over again, otherwise you just go insane. I don’t want to become stale. I want to be creative.”

And dressing up like a Nijinsky or a party clown is being creative?

“I want to put my music across, as far as entertaining is concerned, with everything: costumes and lights.

“It’s a progression with the music and I felt, for want of better words, if our music was getting mature and sophisticated so should our stage act. Our songs needed a different kind of interpretation, and that’s what we’re trying to do.

Mercury’s convinced, as he’s briefly mentioned, that he is a misunderstood cultural innovator.

Inevitably this line leads back to his feelings of animosity and resentment towards the press, and almost in passing he mentions that A Day At The Races was received unfavourably. Critics noted, he says, that there had not been much of development musically.

This, of course, is the crux of the matter. If they are artistically on the decline, then how will his interests in other art forms be beneficial? After all, if they lose their musical impetus will there be any satisfaction pirouetting in an empty hall?

And he thinks these extra-curricular activities have helped him towards composing better material?

“Certainly!” He proudly proclaims. “Something like Bohemian Rhapsody didn’t just come out of thin air. I did a bit of research, although it was tongue in cheek and it was mock-opera. Why not? I certainly wasn’t saying I was an opera fanatic and I knew everything about it.”

“This is it. I just like to think that we’ve come through rock ‘n’ roll, call it what you like, and there are no barriers: it’s open. Especially now when everybody’s putting their feelers out and they want to infiltrate new territories. This is what I’ve been trying to do for years.

“Nobody’s incorporated ballet. I mean,” he laughs smugly, “it sounds so outrageous and so extreme, but I know there’s going to come a time when it’s commonplace.”

BUT WHAT significance will it have for audiences? Call me a cultural clot Fred, but like me, most rock fans probably think Nijinsky was a famous racehorse!

“That’s very good,” he chuckles, kindly indulgent. “Yes, I agree. It’s something I’ll try and if it doesn’t work, well it doesn’t work. It’s something that David Bowie did to an extent: bringing a kind of theatre into rock.”

Indeed. But Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust character was of crucial importance to the musical concept.

“Forget David Bowie now,” he comments, effortlessly dismissing the argument, “because this is totally different.”

“A lot of the music does lend itself to the kind of styles I’m putting across. I just felt I needed a more graceful approach. It’s very close to the music we’re doing. But I know it might be hard to grasp at this moment.”

Although Mercury may appear to exude an air of composed confidence and express a tailored answer to most questions, he is more vulnerable than he believes.

Indicative of this is his frequent use of such effeminate endearments as darling and dear when rankled, and he is unconvincing when attempting to argue a point by alluding to the interviewer’s inadequacies. “You don’t seem to realise…” he will begin.

Of his multifarious talents, mind-reading is not listed in his biographies.

Similarly his image as the gallant, impetuous and high living dandy socialite is obviously more celebrated by the media than Freddie himself.

When his background, for example, is brought into the conversation he is sensitively defensive of his Persian roots and the family ties he has in India.

“O you sod,” he squeals. “Don’t ask me about it. Read my bios. Oh, it’s so mundane. Ask me about something else.”

Another tender area is his own artistic stature. Criticism of his contributions to Queen he painfully bears, but with a smile. And my opinion that on Races there are only two worthwhile songs, Tie Your Mother Down and White Man, causes Freddie to exhibit strong loyalty to Brian May, the songs’ writer, and the other two Queens.

His major defence of the Races album is that it was meant to be a companion piece to A Night At The Opera; which is basically his justification to counter critics who, like myself, say the set is an unimpressive shadow of its predecessor.

“I felt,” he explains somewhat dubiously, “it needed two albums to put across the kind of music that we got on A Night At The Opera, and maybe it was a slight progression.

“Now, we’ve done enough. We’ve been talking about it, and I feel the Queen style of well-produced or production sort of albums is over. We’ve done to death multi-tracked harmonies and, for our own sakes and for the public’s, we want to go on to a different sort of project. And the next album will be that.”

Opera and Races title concept – after all they’re the names of consecutive Marx Brothers films, and the respective packaging (white and black sleeves respectively with similar art work) – support this theory.

But Queen have a reputation for being innovative with each album they make, and Mercury’s elaborate arguments that they recorded Races in an attempt to avoid another musical departure seems contrived.

“Oh dear. Well, I’ll tell you we haven’t. Whereas people have been used to us making drastic changes this is just a subtle change.

“We certainly haven’t dried up. Okay, we might have taken a breather on A Day At The Races, if you like. I don’t think it lacked quality. We maintained our standards.

“We’ve gone through stages in leaps and bounds and we’ve sort of come to a rest for a while. Two albums is not bad. My God, a lot of people have to do it.”

Apparently Freddie would rather discuss the future. Since the completion of their Euro-tour with two concerts at Earls Court they now have three weeks to write and arrange material for their next album, although as Mercury admits, “We haven’t written a damned thing yet.”

This, or course, is not a major disadvantage because the new working procedure amounting to two months studio time rather than the usual four, will ensure, he claims, a refreshing rejuvenation of their artistic spirit. In short, it is a challenge – he enthusiastically says.

One suspects from what he ways that Mercury is determinedly ambitious, and that he is not totally satisfied with his role within Queen. Recently he has been producing other artists’ records on his own, and similarly Taylor has worked solo, recording his own single.

“If I felt the band wasn’t going any place,” he answers easily, “it would have been disbanded.”

“Why do you think Hollywood was so successful? It’s the kind of lifestyle,” he justifies, “I’ve grown up with.”

“We will stick to our guns,” he says, adding firmly, “and if we’re worth anything we will live on.”

The if hangs ominously in the ensuing silence.