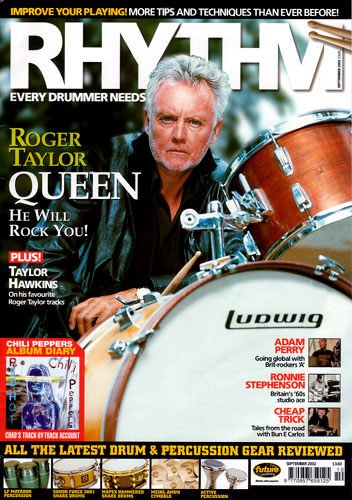

09-XX-2002 – Rhythm Magazine

The Power and the Glory

The Power and the Glory

Interview by: Adam Jones

Occupant of the drum throne with the grandest band in rock, Roger Taylor powered Queen throughout their illustrious career, in the process contributing to some of the most outstanding recording of the last 30 years. A decade after the band’s untimely demise, their popularity shows no sign of waning. Rhythm salutes a true monster of rock…

Queen were and remain a phenomenon like no other. Possibly the greatest rock group ever, they created their own sound – a mock-operatic fusion of macho rock and vaudevillian fey delivered with outrageous theatricality. Standing head and shoulders above their peers, Queen were always bigger and better than anyone else. Fronted by the impossibly charismatic Freddie Mercury, they were driven by Brian May’s distinctive multi-layered guitar and steered by the intelligent and musical rhythm section of Roger Taylor and John Deacon.

A string of classic ‘70s albums – Sheer Heart Attack, A Night At The Opera, A Day At The Races, News Of The World and Jazz among them – underlined their accomplished musicianship and original songwriting skills, while their muscular and ever more flamboyant live shows put beyond all doubt their ability to excite and entertain. And they moved with the times: they ushered in the ‘80s by releasing ‘Another One Bites The Dust’, a slice of funk genius that became the biggest-selling single of the year in America.

In the mid-‘80s the band began touring further afield from the UK and America and in the process broke into massive new markets. They were particularly popular in South America, playing to over a quarter of a million people at the Rock in Rio festival. The experience proved fruitful. After returning to England, they appeared at Live Aid in the summer of 1985, and showed the world how to whip a stadium full of people into a frenzy in the space of 20 minutes.

The years that followed this show-stopping performance were some of the band’s most successful. With all four of its members writing the songs equally, another batch of hit-packed albums littered the charts and sell-out tours of the grandest scale soon ensued. And then, in 1991, it ended abruptly with Freddie Mercury’s untimely death. The shattered remaining trio vowed to celebrate Freddie’s life in the style to which he was accustomed, and in the spring of 1992 staged the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert. Once again a sold-out Wembley Stadium reverberated to the sound of Queen’s anthems, while an international audience of one billion watched around the world. Simultaneously ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ topped the charts again in the wake of its starring role on the soundtrack to the smash-hit Wayne’s World movie.

In 1994, the three surviving members reunited to add music to vocal tracks that Mercury had recorded on his death bed, culminating in 1995’s Made In Heaven album. Since then things have been understandably quiet on the Queen front. John Deacon has retired altogether from the public gaze, leaving Roger and Brian May the sole representatives of Her Majesty’s Purveyors Of Rock.

It is fitting, therefore, that the eponymous sovereign herself enlisted the skills of the duo to help celebrate her Golden Jubilee in June of this year. Indeed, their sparkling performance at Party At The Palace showed that the band have lost none of their popularity. If anything, there is a massive Queen revival under way: the West End musical We Will Rock You has weathered savage reviews to become a huge box office hit, while the Greatest Hits I, II & III collection has raced into the top ten.

Throughout the years, Roger Taylor has added his individual touch to some of the finest moments in popular music. His performances are always perfectly weighted – restrained and full of subtle flourishes in the right places, yet delivering full-on power when required. His trademark meaty fills – that instigate involuntary bouts of air-drumming in listeners – demonstrate his musicality, while his more demented kit flurries, unleashed when suitable opportunities are presented, are evidence of his great showmanship. Still passionate about drumming and music, Roger met Rhythm at his house in Surrey.

Rhythm: The phrase ‘enduring popularity’ could have been invented for Queen…

Roger Taylor: “It never ceases to amaze me. We try to stay a bit visible occasionally, but we seem to have had a run of high exposure just lately.”

Does the loyalty of your fans surprise you?

“I think of it on a two-tiered basis: there are the hardcore fans that have been amazingly loyal for many years. Some of them used to follow us all over the world – I used to think that they were bonkers, but they were very nice and very loyal. And then there’s the mainstream audience who see us playing a big event on television and say, ‘Oh, they were good’.”

Speaking of which, how was the Party At The Palace? You looked as though you were enjoying yourself…

“Yeah, it was good. Brian and I take things a bit more in our stride now. It was quite a lot of work, though, because we were both playing on quite a few different things, so we had to keep focused. We had to do the intro, then I had to go on very quickly with Phil Collins for ‘You Can’t Hurry Love’, and then we did our own set. And then McCartney asked us to play with him, which was nice, but it was right at the end, so I had to keep sober all the way through it! Playing ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ was interesting because I hadn’t played the middle section since we’d recorded it. We never used to play that part live, because there were only three of us singing and you need 30 singers to do it. I had to study the parts – I actually asked Tony Bourke, who plays it in the show (We Will Rock You), ‘What happens here?’ and then it all came back.”

Apart from sharing the same moniker as our monarch, your regal connections go back another 25 years, don’t they?

“We played at Earls Court as part of the Silver Jubilee celebrations in 1977. Earls Court is the worst place to play that I can remember – I would never, ever play there again. It’s just a great monstrous echoing barn, with absolutely no soul or atmosphere whatsoever. The only thing I ever saw that worked there was The Wall – of course, that’s a monstrosity in itself, so that’s why. I can’t believe that it was 25 years ago. I remember hating it – it’s such an unwieldy place to play.”

I trust that the Party At The Palace was a happier event for you?

“Definitely.”

Take me back to the young, pre-Queen Roger Taylor…

“I grew up in Norfolk, in Kings Lynn, until I was seven. Then my father got a job in Cornwall, so we moved down to Truro. My father’s family were from Cornwall, so it was a sort of return home for him. By then I was banging on saucepans. I had my mum’s saucepans – small, medium and large – and a big pair of wooden knitting needles. That was my very first attempt at drumming. There was a moment, when I was about eight, when I began playing the ukulele with no chords, but drums were my first instrument because that’s what I was good at. I did try the guitar but it was so difficult. Drumming came naturally to me – I always found it sublimely easy, and to play guitar properly was anything but.”

And did you begin playing in local bands?

“Yeah, I started getting really interested when I was 12 or 13 years old. I played throughout my schooldays and made a bit of good pocket money out of it. We’d do all the local villages and towns, in town halls. And I loved it, I just absolutely loved it.”

What prompted your move to London in the late ‘60s?

“I moved up to study at college, but I really wasn’t interested in an academic career – I wanted to be a musician and in a band.”

What was it like playing around London in those years?

“It was very student-orientated. I met Brian after only a couple of weeks in London. We met in the Student’s Union Bar, Imperial College, and immediately clicked.”

So, you decided that Brian was a man that you could do business with? “I just thought, ‘This bloke has got a special touch which I’ve never heard’, and you can only describe his playing as beautiful: a real feather-light touch and vibrato – he really made his instrument sing. And we liked the same people, with a few exceptions.”

“He’d never met anyone before who could actually tune drums – he wasn’t even aware that drums were tuneable. He just thought that they were things that you hit – typical guitarist. Guitarists only think about the guitars, that’s all they hear when they listen to a record. Anyway, we started our band in the jazz room at Imperial College, and it all just grew out of that, really. We were doing all sorts of student gigs at universities – we even ended up at the Albert Hall with a very strange line-up: The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, Joe Cocker, Spooky Tooth and Free.”

What was the name of your band?

“Smile – it was just Brian and I with another guy called Tim.”

Cue your meeting with the young Freddie Mercury…

“Freddie came over with our singer one day; they were both at Ealing College Of Art, and he just became one of the circle. He was full of enthusiasm – he had long, black, flowing hair and this great dandy image, and was great fun to have around. He got himself into a couple of bands, and our band broke up and then his did, and the natural thing was to come together, so we did. We had difficulty finding any bass players who would fit – until we found John.”

Did it start to really feel right then?

“It felt like a unit – maybe because we’d all been students, I don’t know. It was very democratic – Freddie had good leadership qualities, but he always insisted that everybody had a vote. There was lots of arguing, but it was mainly friendly. Back then Freddie was the real driving force because he was the most prolific writer.”

Did his vision ever surprise you?

“Many times. His understanding of harmonic structure was phenomenal. He was a brilliant musician, which most people forget among all the dressing up and ridiculous costumes and his outrageousness. Quite a visionary, really.”

The general consensus in that you were the best-looking member of this band by some degree…

(Laughs) “Well, I definitely disagree with that!”

…So to be stuck at the back…

“That never bothered me – we always thought ‘You have a job to do’. Freddie’s job was to be the frontman, the visual focus for the audience, and he was brilliant at it. And then we all had our own functions and I think that we were quite happy. I never wanted to be at the front.”

What was the high point of Queen for you?

“Well, there are a lot of high points, really. We always thought of ourselves first and foremost as a live band. Although we sold a lot of records, we enjoyed playing live. Live Aid was a high point – for everybody it really was a great day – but we had particular shows which were good. I think when we were touring Argentina we were absolutely at our peak and pretty unbeatable.”

So what exactly is it like to play to a quarter of a million people?

“It’s impressive. Basically you’re just so focused that you want to do it right and make sure that things don’t go wrong, so most of the mental energy goes on that. There are so many people that it’s just a mass, so you really have to make sure that you get it right, that it comes over and it works.”

But how do you mentally prepare for that sort of scale? Is it a lot of rehearsal?

“No, there’s no extra rehearsal – it’s just getting used to playing that kind of big audience. It’s a different sort of art. I think that we were good at it, particularly because Freddie was so good with the grand gesture – he knew how to work the audience, how to communicate and make everybody feel like it was one big party. To an extent U2 have that, they’re very good. Pink Floyd are also good at big shows, they have such monstrously huge productions – very impressive lights that go wonderfully with the music.”

Did you sense that you would get so big?

“We always liked the idea of doing big stuff, and the bigger the better. Maybe we were ambitious. Maybe we needed to gratify our egos. I don’t know, but the idea of communicating with that number of people was very exciting.”

Apart from the obvious one, were there any low points for you in Queen?

“There was a point where we’d got to incredible popularity in America, around the time of The Game, but then we really dipped. We made a couple of strange choices for albums – we went down a sort of funk avenue with the slight dance angle, and that was everything that our US followers hated. I felt at the time that we were going too far down that road, but because we’d had a huge hit with ‘Another One Bites The Dust’, we thought, ‘Oh, this is our new direction’ but it wasn’t really us. The lowest point of all was when we found out about Freddie’s condition.”

Was it difficult to separate the personal and the professional sides of your relationship with Freddie when it became obvious he wasn’t going to get better?

“We became closer. He wanted to work – he wanted to occupy his mind and his days. So we spent long, cloistered periods abroad, just backing him up and forming a protective wall. It was actually a good time in a way, because we felt very close – the closest we’ve ever been. In the end Freddie was doing all the singing in the control room because he couldn’t walk into the studio. The last album, Made In Heaven, was very hard work, because Freddie had died and we had to fill in the holes. I think it’s a very strong album – certainly the most emotional album.”

It must have been a tough time for you.

“It was a very difficult period. When you look back, it’s actually much worse – you go around pretending that it’s not that bad, but it was five years before any of us really realised the tremendous effect that it had.”

Did the reaction to his tribute concert surpass your expectations?

“I thought that it was great, the audience was wonderful and I think that we put together a hell of a show in about two months. It actually helped me at the time because I threw my whole being into it and it took away a bit of the pain.”

As an all-round musician, did you ever feel restricted by the drums?

“We were very much a team, Brian would play piano here and there and I played rhythm guitar on some things. John played keyboards and acoustic guitar on ‘Crazy Little Thing’, for instance, so we weren’t that restricted. Also, as time went on we all became writers. At first, Freddie and then Brian were the dominant writers, but then John and myself came up, so all four of us were contributing. By the end things were very equal. I was one of the three singers as well, so there was an awful lot to do. I did some solo work too, because there wasn’t enough space on the Queen albums for all my ideas. I just thought, ‘Well I could do a bit more, do it solo’.”

You’ve always had a good idea of what a set of drums can bring to a song.

“That’s something that we learnt very quickly in the studio. The tendency in those days was for everybody to be a virtuoso – to show off on your instrument. But to me you were playing a song, and so the instrument should complement the song in every possible way. Obtrusively or unobtrusively, you should play the song, and not think about dots or bars. That’s what I tried to do. The more that you just let yourself flow with the song and understand it – how the tempo should be, if it should push here – the more you play with it. I have a desperate mistrust of dots – you can never put in the dots what is needed. The language simply isn’t good enough.”

You play from the heart?

“Absolutely, and I think that you should just watch the song and learn the song.”

And use your ears?

“Yeah. Maybe the beat should be a little bit behind, maybe you should push, whatever. It’s all about feel really.”

Your trademark ‘big sound’ dates back to early Queen. How did it come about?

“I’ve always liked to use big drums. I’ve got nothing against the Stewart Copeland kind of thing, which is very good in its own way, but I was always into the ambient sound of a drum kit. I like big, tuneful drums with a natural room sound, so the whole kit sounds balanced. I wanted it to sound as though it were in a room and you were hearing the reverberation from the walls. Sometimes you would achieve that with machines and sometimes you’d get the right room and it sounded great. Obviously, it changed with different songs – ‘Bites the Dust’ was as dry as you can get, but typically I would have a big, fat, ambient, monster drum sound.”

As a self-taught musician, were you inspired by any particular drummers?

“I used to like the jazz drummers because of their beautiful fluidity. I love Mitch Mitchell – I think that some of his stuff on the first Hendrix album Are You Experienced is just sublime, absolutely floating over it all. Of course I love Keith Moon, but probably above all, I love John Bonham. It’s a pretty predictable pantheon, but let’s face it, they don’t make them like that lot any more. Although there are some great guys around…”

Is there anyone from nowadays that you think stands out in a similar way?

“I think that McCartney guy – Abe Laboriel Jr – is really good, but my own personal favourites would be Taylor Hawkins and Dave Grohl. To have them both in the same band is incredible – when they play together it’s like dynamite. Dave is brilliant, and Taylor, he’s just like a firestorm. Those two play phenomenally.”

Over to the musical, We Will Rock You. Do you see it as a fitting tribute to the band?

“It’s a mainstream piece of entertainment. It’s not meant to be biographical at all. It’s a lightweight story that has a few salient points and the music comes over very well. I think it’s a great night out – it’s like a sort of adult panto with great music. Every night there’s a fantastic ovation at the end and people come out buzzing. It got the worst reviews I’ve ever seen, but they’re basically missing the point: it’s a light-hearted piece – it’s not something to get worked up about.”

Queen’s single-mindedness was as big a factor in their success as their musical talent. Do you think that a band like Queen could prosper in today’s music business?

“I think the answer is ‘Yes’, but they would have to get around having somebody like Simon Cowell or a record company of that ilk controlling them and marketing them into talcum powder. The very idea of them thinking that they know more about music because of their market research and demographic nonsense – ‘They’ve got a hot band, let’s get one like that’ – is rubbish. But there are labels that do respect the artists’ creativity, so proper bands that actually excite and break rules instead of just following like homogenised sheep could succeed with the right company behind them. Bands like Radiohead have complete creative control, and they are totally uncompromising with it.

“I don’t personally like their latest stuff very much: I thought the best record that they did was The Bends – what a fantastic record. But they’re treading their own path, that’s the main thing. At least they’ll be interesting, even if they’re uninterestingly interesting!”

What’s on the horizon for Roger Taylor?

“At the moment I really need a holiday, but there might be something new in the pipeline. I’m enjoying doing the odd thing like Parkinson, which was seat-of-the-pants live stuff with the show’s cast, and the Party At The Palace. And Brian and I did a show in Amsterdam – 150,000 people turned up, and we thought ‘Wow!’ We’ve been working very well together, so we might think of doing something – the dinosaurs might creep out of their cage…”