09-05-1997 – Jerusalem Post – A Lying Floozie

THE FREDDIE MERCURY STORY: Living on the Edge by David Bret. London, Robson Books. £19.95.

Empty spaces. What are we living for?

Abandoned places. I guess we know the score.

On and on, does anybody know what we are looking for?

The show must go on. The show must go on.

Inside, my heart is breaking. My make-up may be flaking.

But my smile stays on.

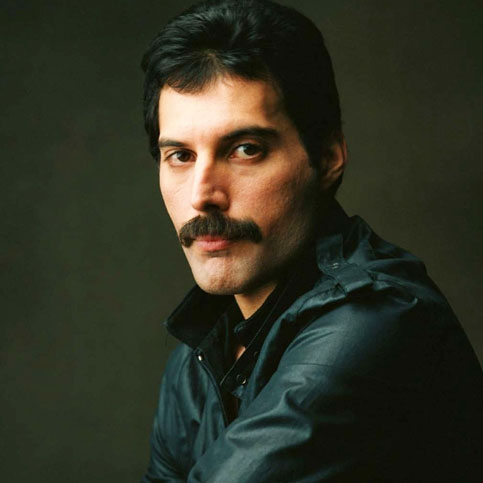

Freddie Mercury wrote these words of the 1991 hit “The Show Must Go On” as he was dying of Aids, his body crumbling, but his talent and humor still intact. Several months later, on November 24, Mercury died at age 45. By then he was regarded as the greatest singer in rock; and unlike most pop stars based in the US or Britain, he left behind a truly international audience of fans.

Mercury was first a singer and then a rock ‘n’ roller. He was born Faroukh Bulsara on the island of Zanzibar, the eldest child of a Persian clerk. The family were Parsees, followers of Zoroaster, direct descendants of those Persians who had fled to India 1,200 years ago to avoid persecution by the Moslems.

Eventually, little Faroukh was sent to a prestigious English boarding school outside Bombay and became known as Freddie. He quickly took to rugby, cricket, and football and adored boxing and table tennis. His early influences were such singers as Lata Mangeshkar, called the nightingale of India, and the legendary Egyptian singer Oum Kalthoum.

When he was 14, Freddie had his first love affair – with a 17-year-old boy. Over the years, he would so outrageously flaunt his gay lifestyle that most of his fans and critics thought it was a put-on.

The Bulsara family fled to London along with thousands of other British and Indian nationals when Zanzibar broke free of British rule and merged with Tanganyika to form Tanzania. In London in the Sixties, Freddie went to Ealing College of Art, the alma mater of such rock luminaries as Pete Townsend and Ronnie Wood. He dispensed with his Parsee tradition, distanced himself from his family, and developed a consuming passion for rock guitar legend Jimi Hendrix. By 1964, the young immigrant was making the rounds of rock bands and met his collaborator and guitarist Brian May. Later, Roger Taylor joined Freddie, and the two sold rags in Kensington Market. Soon, Freddie was wearing his merchandise, walking around in feather boas, wide-brimmed hats – his fingernails lacquered black.

By 1970, Bulsara had changed his name to Mercury, the messenger of the gods blessed with skill and eloquence. His new band was called Queen, and he made it clear that it was a reference to British royalty rather than to gays. May was on guitar; Taylor was on drums and a year later John Deacon joined them on bass.

At first, Queen was lumped with the other glamor bands of the early and mid-1970s such as David Bowie, Cheap Trick, Thin Lizzy and Mott the Hoople. But Mercury was no glitter boy. His range was way past anything known in rock. He could hit an E above high C, something heard only in opera. He could sob like Piaf and enunciate like Barbra Streisand.

Mercury and the rest of Queen could also write great songs. In 1976, early in their career, they released “Bohemian Rhapsody,” with a multi-dubbed 180-member vocal section, the gospel-like “Somebody to Love,” the ballad “Love of My Life,” and the funky “Another One Bites the Dust.” And there were the songs that became anthems in soccer stadiums and political rallies around the world, such as “We Are the Champions” and “We Will Rock You.”

Ironically, the most important person in Mercury’s life was a demure Englishwoman named Mary Austin. It is not certain whether they were lovers but their relationship was intense and lasting. As Mercury put it, “We look after each other, and that’s a wonderful form of love.”

In 1987, Mercury embarked on a project that left his fans wondering whether he had gone mad. He had long been a fan of vocal music although he found the opera stage overbearing. His first step was his collaboration with the Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballe, who was 13 years his senior and had once worked in a handkerchief factory in her native Barcelona. Mercury wrote and played music in concert for Caballe, including the now famous operatic “Barcelona,” written for Expo ’92, the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America.

The budding partnership was rocked by Aids. The disease was killing practically all of Mercury’s friends and lovers. It was only a matter of time before his turn came. By 1987, Mercury had tested HIV-positive and was believed to have already developed the disease.

Mercury’s goal was to keep his dread sickness secret, even from his band. He cut down on his intake of vodka but those close to him noticed the dark blotches on the side of his face, then arms and neck. Mercury plunged into his work, recording but no longer performing, buying anything he pleased for himself and his friends.

He was hounded by the British tabloids which didn’t believe his constant denials of illness

“The last thing he wanted was to draw atttention to any kind of weakness or frailty,” Queen drummer Taylor recalls. “He didn’t want any kind of pity.” On November 23, 1991, Mercury announced he had Aids. The following day he died. Queen never tried to replace its lead singer.

David Bret’s description of Mercury’s early life and influences is excellent. It is when Mercury becomes a star that the books turns weak.

Bret is too busy giving a blow-by-blow account of Mercury’s recording and performing career to provide us with much insight into the life of a rock legend who led an openly gay lifestyle. There is little insight into his relationships with his straight band members, family and friends.

Most of all, there is only a whiff of a suggestion of Mercury’s abject loneliness, exacerbated by the stardom he achieved. We know he was a heavy drinker and drug user, but we don’t know much more.

Perhaps the author had little to go on. The public Mercury was a lying floozie who called everyone dear and played a role until the end.