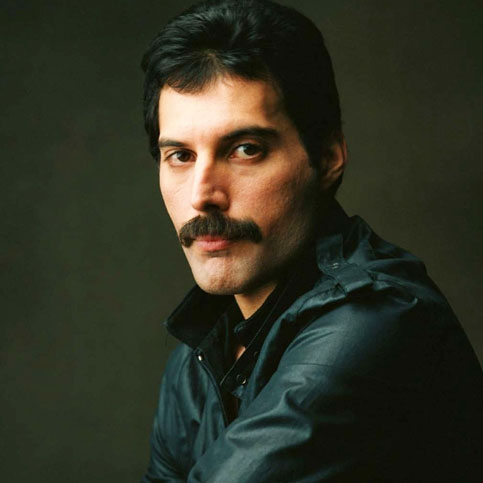

01-09-1992 – Rolling Stone – Freddie Tribute

Queen singer is rock’s first major AIDS casualty

FREDDIE MERCURY, THE OUTLANDISH frontman for Queen, whose worldwide hits like “Bohemian Rhapsody” and “We Are the Champions” combined gaudy theatrical pomp with heavy-metal bluster, became the first major rock star to die of AIDS when he succumbed to complications from the disease on November 24th at his London home. He was forty-five years old.

Mercury, whose real name was Frederick Bulsara, had not performed with Queen in concert since 1986. He had become a virtual recluse over the past two years, yet he repeatedly denied reports that he had contracted AIDS until the day before his death.

“The time has now come for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth,” he said in his statement, explaining that he had waited so long to make the announcement because “my privacy has always been very special to me.”

Although Mercury’s condition was long rumored in the tabloid press and virtually an open secret in the music industry, his death still startled many fans and colleagues. Bouquets from Elton John, David Bowie, U2, Ringo Starr and the Scorpions adorned the West London Crematorium, where a brief funeral service in the Zoroastrian faith was held for his family and a few close friends, including the surviving Queen members, Brian May, Roger Taylor and John Deacon.

“Of all the more theatrical rock performers, Freddie took it further than the rest,” says Bowie, who collaborated with Mercury and Queen on their 1981 hit “Under Pressure.” “He took it over the edge. And of course, I always admired a man who wears tights. I only saw him in concert once, and as they say, he was definitely a man who could hold an audience in the palm of his hand. He could always turn a cliche to his advantage.”

Beginning in the early Seventies, the flamboyant Mercury – who cited Jimi Hendrix and Liza Minnelli as his main influences – led Queen through eighteen albums that sold 80 million copies worldwide, amassing almost a dozen U.S. hit singles, including his campy “Killer Queen,” the Elvis spoof “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” and the bass-heavy anthem “Another One Bites the Dust.” Queen’s popularity nose-dived in the United States during the Eighties, but the group remained popular in England and around the world.

Queen laced British glam pop with swooping arias, corny vaudeville themes and heavy-rock bombast, but it was Mercury’s wicked taste for wretched excess that set the band apart. “Freddie was clearly out in left field someplace, outrageous onstage and offstage,” says Capitol-EMI president and CEO Joe Smith, who headed Queen’s American label, Elektra Records, at the peak of the group’s success. “He was the band’s driving force, a tremendously creative man.”

Elektra’s release of Mercury’s overwrought, six-minute mock opera “Bohemian Rhapsody” – complete with a goofy choir chirping “Mama mia, Mama mia” – was only one example of his musical extravagance. He was even more extreme when it came to his concert performances, appearing in leather storm-trooper outfits or women’s clothes and taking an arch, gay-macho stance that both challenged and poked fun at the decidedly homophobic hard-rock world.

Offstage, Mercury was known for his wild antics and the lavish gifts he bestowed upon friends. To celebrate his forty-first birthday, for instance, he flew eighty pals to an exclusive hotel on the resort isle of Ibiza, where they were treated to fireworks displays, flamenco dancers and a twenty-foot-long cake carried by waiters dressed in gold and white costumes. “All I can remember about the whole time we were making records and hanging out was that it was like one continuous party,” says producer Roy Thomas Baker, who worked on five Queen albums.

Excess also defined Mercury’s sexual lifestyle. Though he lived with girlfriend Mary Austin for much of Queen’s early career, he often boasted about his numerous trysts, claiming he’d had “more lovers than Elizabeth Taylor.” A former associate remembers seeing a line of men dressed in sailor suits marching into Mercury’s dressing room after a concert date. Once the AIDS epidemic began taking its toll, however, he panicked about his promiscuity; he said that he refused to tour the U.S. for fear he might contract the disease. But as late as 1987, Mercury was telling interviewers that he had tested negative for HIV.

BORN SEPTEMBER 5th, 1946, ON THE AFRICAN island of Zanzibar, to a British-government accountant and his wife, the young Frederick Bulsara was raised in Bombay, India, and moved to England with his parents shortly before reaching his teens. Earning a degree in graphic design at art college during the late Sixties, he joined a local blues-rock group called Wreckage; he dubbed himself Freddie Mercury after the mythological messenger of the gods. Around this time he also became friendly with members of Smile, a power quartet featuring guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor.

“Freddie always looked like a star and acted like a star even when he was penniless,” says May. “The first thing I remember about meeting him was that he seemed like a gypsy. He was nominally living with his parents but stayed with whomever he wanted. He invited me round to his house, where he had this little stereo, and played me some Hendrix. Freddie said, `This guy really makes use of stereo,’ so we went from one speaker to the other, finding out how he produced those sounds.”

Smile soon split, and the three struggling musicians started a new band that Mercury christened with his own regal touch. “I’d had the idea of calling a group Queen for a long time,” he said in a 1977 ROLLING STONE interview. “It was a very strong name, very universal and very immediate; it had a lot of visual potential and was open to all sorts of interpretations. I was certainly aware of the gay connotations, but that was just one facet of it.”

Recruited through a classified ad, bassist John Deacon filled out the new quartet, which rehearsed in private for nearly two years while some of the members finished school. Its 1973 debut album, Queen, went unnoticed, but its more eclectic second album, Queen II, released in early 1974, made the British charts. The group’s third effort, Sheer Heart Attack, finally broke the band in America on the strength of a hit single about a high-class call girl, “Killer Queen.”

Although a 1975 headlining tour in the U.S. was interrupted because Mercury suffered from voice problems, a trek to Japan that year proved overwhelmingly successful. “It was like the second coming of the Beatles,” says Jack Nelson, the group’s first manager. “Somehow, word got out we were on the Hikari Express, and the train stations were mobbed with people beating on the railway cars. When the band played Budokan, the audience rushed the stage like a tidal wave. We had barricades in front with sumo wrestlers behind them, but the crowd just climbed over en masse.”

Recharged by that Japanese invasion, Queen began recording A Night at the Opera, an album highlighted by Mercury’s over-the-top “Bohemian Rhapsody.” “I went over to Freddie’s apartment,” says Roy Thomas Baker, “and he played me the first part on piano, which was like a ballad. Suddenly he said, `Now this is where the opera section comes in, dear,’ and I fell down laughing. It was originally supposed to be five or ten seconds, but when we started the sessions, it went to a minute, then more. We just went `More, more, more,’ until the recording head on the tape machine literally broke off.”

The band’s next album, News of the World, went platinum in the U.S., thanks to a double A-side single pairing Mercury’s “We Are the Champions” with May’s “We Will Rock You.” Both songs became instant hits. Around the same time, however, Queen incurred the wrath of the emerging punk movement. While recording “We Will Rock You” at Wessex studios, Mercury came face to face with Sex Pistols bassist Sid Vicious. “So you’re this Freddie Platinum bloke that’s supposed to be bringing ballet to the masses,” Vicious snarled, prompting a completely unfazed response from Mercury: “Ah, Mr. Ferocious, we’re trying our best, dear.”

Ignoring the venom of punks and other critics, the band stayed as extravagant as ever. To celebrate Queen’s album Jazz, Elektra and EMI, the group’s British label, sponsored the rock party to end all rock parties in New Orleans, with Mercury’s orchestrating every last detail. The $200,000 bash was a tribute to debauchery, a Sodom-and-Gomorrah-style orgy complete with dwarfs, transvestites, snake charmers and a stripper who puffed cigarettes with her crotch. There were ample servings of champagne and more exotic intoxicants.

“It was definitely a Freddie party,” says Joe Smith. “He was testing the limits of what he could get away with, and people were kind of dazed, because there had never been anything quite like it.”

Queen then reigned as one of the biggest rock acts in the world, a position solidified with “Crazy Little Thing Called Love,” from 1979, which became the group’s first Number One single in America. John Deacon’s thumping “Another One Bites the Dust” also topped the U.S. charts and was adopted as the Detroit Lions’ fight song. But only three more singles – “Under Pressure,” “Radio Ga Ga” and “Body Language” – cracked the U.S. Top Forty after that. Some believe Queen’s fall began after Mercury changed his look, cutting his hair short and growing a mustache.

“When Freddie grew his mustache, people started throwing razor blades onstage,” says a former associate. “They began to suspect he was gay, and that’s when they turned on him.” The backlash intensified in 1984 when he dressed as a big-bosomed housewife for the video to “I Want to Break Free.” Mercury contested press reports that he was homosexual. “If I tried that on,” he said at the time, “people would start yawning, `Oh, God, here’s Freddie saying he’s gay because it’s very trendy.'”

“When we did the video in drag, everyone in England thought it was very funny, but America hated it and looked on it as some gross insult,” says May.

Queen also took a drubbing for its decision to play Sun City, the plush resort in Bophuthatswana, a bogus “tribal homeland” in South Africa. “There’s lots of money to be made,” said Mercury shamelessly. The move placed Queen on a United Nations blacklist for breaking the cultural boycott against the racist regime. The self-described “apolitical” band members justified their action by saying that they were antiapartheid and that they had performed to mixed audiences in Sun City, but the incident still tarnished their image.

Despite its loss of stateside credibility, Queen was hardly without an audience. In 1981, Queen became the first rock act to play stadiums in Argentina and Brazil, where the band had acquired an enormous following.

Other musical diversions – including Queen’s soundtrack to a cheesy remake of Flash Gordon and a Mercury solo album titled Mr. Bad Guy – hardly broke new ground. Far and away Mercury’s greatest achievement during this period was a shattering performance at Live Aid, the 1985 benefit concert for African famine relief. On a day filled with sets by Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, Madonna and even a reunited Led Zeppelin, some of the most dynamic moments came from Mercury, who had rehearsed diligently with Queen on a tight, roughly fifteen-minute overview of its greatest hits.

“The rest of us played okay,” says May, “but Freddie was out there and took it to another level. It just wasn’t Queen fans – he connected with everyone.” In Queen’s video autobiography, Magic Years, Live Aid organizer Bob Geldof called it “absolutely the best band on the day, whatever your personal preference.”

“It was the perfect stage for Freddie,” Geldof added. “He could ponce about in front of the whole world.”

Follow-up dates in Eastern Europe and the U.K. led up to a 1986 Knebworth Park concert, the group’s last hurrah onstage. Although Mercury continued to record with Queen until his death, he worked on outside projects as well, including a gooey cover of the Platters’ 1955 oldie “The Great Pretender” and an operatic duet with Spanish diva Montserrat Caballe. He also penned a few songs for Time, a stage musical produced by Dave Clark, formerly drummer for the Sixties group the Dave Clark Five.

Fittingly enough, it was another performer with a taste for pomposity – white rapper Vanilla Ice – who gave Queen its biggest boost in recent years by stealing a sample of “Under Pressure” for his annoying hit “Ice, Ice Baby.” More renewed interest came as Hollywood Records, a fledgling label funded by the Walt Disney Company, bought North American rights to the entire Queen catalog, as well as four new albums, for an estimated $10 million.

In February 1991, to celebrate Innuendo, the first new album released under the deal, Disney held a gala reception aboard the Queen Mary cruise liner in Southern California. Two thousand music-industry types feasted on overflowing buffets of shrimp, lamb chops and rich desserts. There was entertainment provided by mimes, magicians, jugglers and other acts, capped by an amazing fireworks display that lit up the sky to the booming strains of “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Like the New Orleans bacchanalia held a decade before, the Queen Mary bash was obviously “a Freddie party.” Except this time around, the guest of honor was nowhere to be found. Brian May and Roger Taylor, the only group members who attended the soiree, delicately dodged questions regarding their lead singer. But both men knew what many of the guests were only whispering about – their once-robust friend, who always believed in living life to the hilt, was slowly dying of AIDS.

MERCURY SPENT MUCH OF HIS LAST years sequestered within the confines of his sprawling Edwardian mansion in London’s swank Kensington district. The three-story red-brick building, which Mercury called his “dream home,” had been completely gutted when Mercury purchased it and then painstakingly decorated over time with expensive gold antiques, Hokusai woodcuts, deco Erte prints and other objets d’art.

As the soulful voice of Aretha Franklin – Mercury’s favorite singer – wafted from his stereo system through the halls of the twenty-eight-room mansion, the now-gaunt singer would snuggle in bed with his favorite Persian cats and try to carry on in the face of his illness. He chose not to abandon his music and, according to one close friend, completed several vocal tracks that may be released later as part of a Queen box set or as a posthumous “farewell album.”

Throughout his final months, Mercury was tended to by Mary Austin, who remained his closest confidante even after their relationship as lovers ended. By early November of this year, Mercury’s condition took a turn for the worst. Although doctors specializing in the disease tried their best to comfort him, the singer suffered from pneumonia, which his immune system was no longer equipped to battle. Extreme body aches and blind spells plagued him constantly during his last days.

The gates of his home besieged by the London press, Mercury is said to have finally released his announcement about AIDS the day before he died because of “media pressure.” Austin explains that “he felt he couldn’t be ill in peace.” Although Mercury was drifting in and out of consciousness, Queen spokeswoman Roxy Meade says Mercury personally approved the statement.

“He realized the end was coming, and he faced it with incredible bravery,” says Austin. “The man did suffer, emotionally as well as physically. In the last few days, he couldn’t eat and was under heavy sedation. . . . But he was a great fighter, and that kept him going.” Finally on November 24th, just ten minutes after Austin left his room and a doctor had recently departed, Mercury died with friend Dave Clark at his bedside. “I stayed in there with him, and then he just fell asleep,” says Clark, who described the moment as “very peaceful.”

Tributes poured in from Phil Collins, Diana Ross and Boy George; longtime friend Elton John, who attended the funeral service, was said to be particularly devastated. In Los Angeles, Guns n’ Roses singer Axl Rose also grieved over the loss of the artist he cited as his most important early influence.

Rose, appearing on the Rockline radio call-in show a few days after Mercury’s death, played Queen’s “Who Wants to Live Forever” and recalled how much the singer’s work meant to him. “If I didn’t have Freddie Mercury’s lyrics to hold on to as a kid, I don’t know where I would be,” he said. “It taught me about all forms of music. . . . It would open my mind. I never really had a bigger teacher in my whole life.”

In the immediate wake of Mercury’s death, many others questioned why he had waited so long to make the announcement about his disease. At a London AIDS conference titled Living for Tomorrow, held just four days after Mercury died, one researcher, Dr. Roger Ingham, criticized the singer’s eleventh-hour statement. “Maybe if Freddie Mercury had revealed his illness much earlier, it would have brought discussion out into the open,” he said.

Those close to Mercury feel he waited so long because he was an intensely private man, despite his extroverted stage persona. “Freddie had a fabulous sense of humor and was absolutely outrageous,” says Bryn Bridenthal, who handled U.S. publicity for the group during its glory days. “But when we went out in public he was very quiet. He had the power to vibrate the air around him at will, yet he could also turn it off. He never got caught up in the star thing of wanting to be seen everywhere; what was happening in his own life was more important to him. He wasn’t a big socializer, but he threw the best parties of anyone on the face of the earth, hands down.”

Mercury reportedly donated heavily to AIDS charities during the last years of his life, and following his death there were plans to contribute more money through the re-release of Queen’s music. In Britain, the proceeds of a rush release of “Bohemian Rhapsody” in early December were earmarked for the Terrence Higgins Trust, a prominent U.K. AIDS charity that provides education, legal help and counseling.

“I think the fact that he was so beloved – straight or gay – will focus some people on the fact that AIDS knows no boundaries,” says David Bowie, who questions whether the music world will address AIDS more directly as a result of Mercury’s demise. “He will be missed primarily as a personality, I think, and the cause of his death will become secondary. Unfortunately, there’s still a very juvenile approach to AIDS in the rock community, almost a forced indifference and a desire to carry on the way bands have always carried on.”

David Bubis, West Coast director of the T.J. Martell Foundation, a music-industry-supported organization that funds AIDS, cancer and leukemia research, adds that getting rock stars to participate in AIDS-related events has been very difficult. “Recently, a restaurant in Southern California attempted to raise money for the foundation,” Bubis says, “and they contacted several bands – not to play, just to sign autographs that could be auctioned off. No one was willing to come out. That’s fairly typical in the music industry.”

“Freddie Mercury is not an isolated case, unfortunately,” adds Bubis. “There will be others coming out in the months and years ahead. Hopefully, out of this tragedy, we’ll be able to use the momentum to do something.”